Missed Connections

The labyrinthine fiction of Catherine Lacey.

Catherine Lacey’s Missed Connections

In her most personal work, The Möbius Book, Lacey uses a devastating moment of heartbreak to ruminate on the messy intersections between life and writing.

The characters in Catherine Lacey’s fiction are always running away from themselves. In her first novel, Nobody Is Ever Missing, we meet a woman named Elyria as she’s about to leave for New Zealand with few plans other than abandoning her husband in Manhattan. In Pew, a genderless, ageless, and nameless person quite literally appears one day out of the blue, having spent the night sleeping in a church in a small Southern town, mystifying its members. In The Answers, we follow a woman by the name of Mary Parsons, who in a desperate search for a cure to her mysterious ailments, enrolls in expensive “neuro-physio-chi bodywork” sessions called Pneuma Adaptive Kinesthesia and then takes part in a 24/7 “income-generating experience” in order to pay for them. As we get to know her, we discover that she is not even Mary Parsons but a woman named Junia Stone, who grew up in a religious household in the South from which she’s now estranged.

Books in review

The Möbius Book

Buy this bookBiography of X, Lacey’s most recent work of pure fiction, also revolves around a mercurial figure, or really two, on the run from themselves as much as from others. Upon entering the novel, we learn that we are reading a biography by a writer named C.M. Lucca, who has set out to uncover the details of her mysterious, recently deceased ex-wife’s past and to correct the record left by a competing biography writer. Aptly inscrutable, Lucca’s Tár-esque ex-wife is best known as the famous visual artist “X.” Who is this elusive woman? By the book’s end, her mask has been torn off: We learn that she had up to 18 different names in her various incarnations, each attached to a distinct career and place of residence. These places, too, are not so familiar: In the novel’s alternative history, the Southern states seceded from the nation in 1945. X was born in Mississippi as Caroline Luanna Walker and lived the rest of her life as a fleeing “refugee.”

Is escaping danger any different from escaping ourselves? And if we manage to do either, do we know where we are going? These are the kinds of questions that animate almost all of Lacey’s fiction, including her newest genre-bending work, The Möbius Book. Billed as a “memoir-cum-novel,” it is Lacey’s first explicitly personal book, though it is a work of universal exposition as much as biographical recollection. Meditating on her life after a divorce, recalling her fraught religious childhood, and sorting through the reasons that she writes fiction in the first place, Lacey offers us an experiment in form but also in ideas. As the first half of The Möbius Book tells a fictional story about a friendship in which not all secrets are revealed, and the second half serves as a vehicle to reflect on the dissolution of a romantic relationship, Lacey presents us with a work that functions like a maze: Where exactly the exit is, and how we might navigate the abrupt, unexpected turns, will always remain a mystery.

If we can compare writing books to painting, then Lacey has always viewed the practice as something akin to performance art. The Answers switches tenses halfway through the novel, and Biography of X uses real people’s photographs as well as names and places. Meanwhile, Pew is told via a strange, ambiguous, mute narrator, so seemingly inanimate that many critics have called the book a fable.

Like Lacey’s earlier work, The Möbius Book breaks many of the rules of contemporary fiction. The first half is a work of fiction, the second half a memoir; and by including both but keeping them separate, the book belongs to neither genre. Each half has its own set of identical opening pages featuring a list of previous works and publisher information, and yet the two cannot really be read as separate entities: Each is one-half of the same whole.

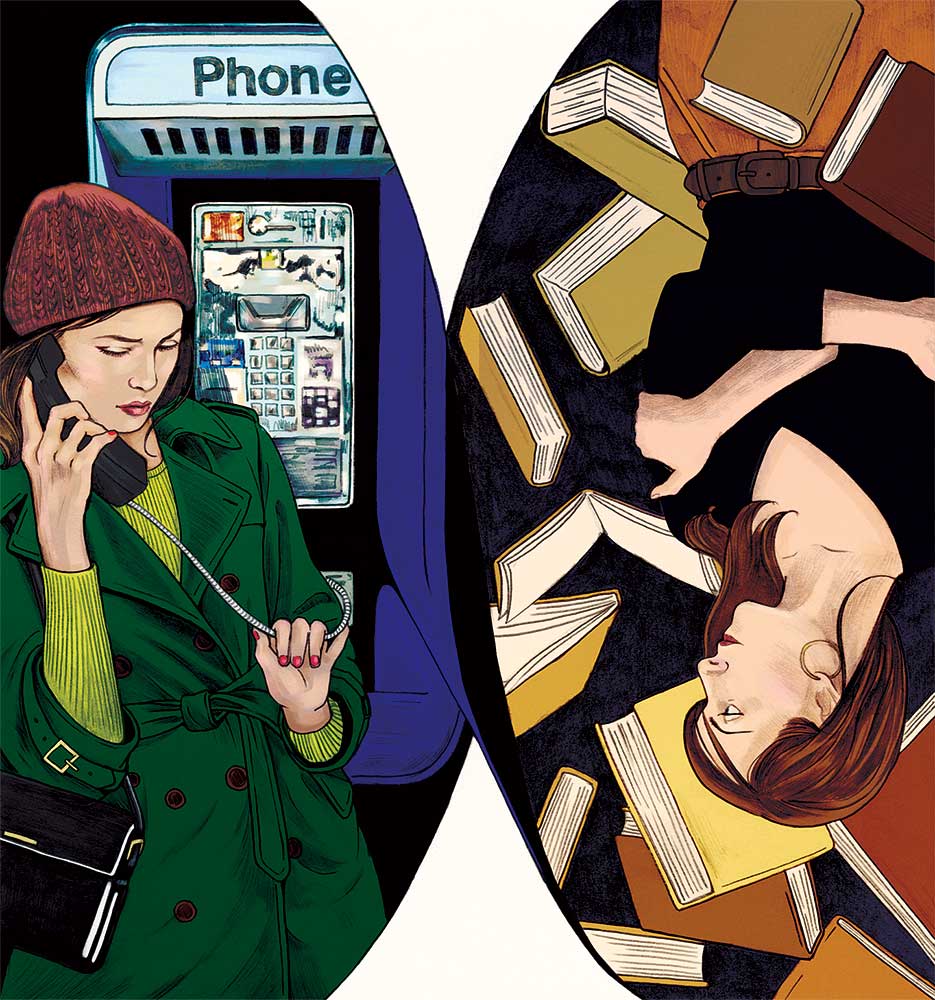

The Möbius Book begins by introducing us to Marie. The resident of an unnamed city and a woman of an unspecified age, Marie gets a call from her friend Edie, who is coming over for a surprise visit on Christmas evening. Though the book otherwise has all the markers of a story set in the present day, Marie communicates exclusively on a landline and a payphone—the proximity to the latter in fact was a reason she chose her apartment: She wanted to be close to “something so irrevocably stuck in the past.”

But things only get stranger after this disclosure: On her way back to her apartment, Marie passes a neighbor’s door and sees a pool of blood. Most people might stop to find out what’s going on, but Marie walks right past; nor does she mention it to Edie when she arrives. The two of them, after all, have plenty of things to discuss. Marie, we learn, has recently gotten a divorce from her wife, whom she cheated on and with whom she has twin children that she no longer sees. Edie, meanwhile, has been through a rough break-up with a manipulative man so domineering that “around him she felt like a child.”

While the two women compare and contrast their relationships, their conversation, almost script-like, is occasionally punctuated by philosophical musings about how things that break can sometimes be repaired; the ambiguity of attraction; and the fleeting, specific nature of memory. But Marie still can’t shake what she saw and has brief moments of private panic: What happened to the couple who lives next door? Did a murder transpire right under her nose?

What actually happens is more bizarre. Toward the end of Marie and Edie’s story, the police appear at Marie’s door and ask her to go down to the station with them. “The story about her weird affair hadn’t made it seem like Marie was truly guilty of anything,” Edie tells the reader as she watches her friend skulk out of the building with her hands behind her back. “But the sight of her getting into a police car does.”

But why is Marie being questioned at all? And how does this relate to her and Edie’s romantic failings? These are questions that we don’t ever get the answers to, even if the analogous stories offer fodder for guesses. Yet when this story “ends,” and after we peruse the acknowledgments and the “works consulted” page—the latter featuring everything from Maggie Nelson’s Bluets to the musician Bad Bunny’s reggaeton album Un Verano Sin Ti—we have no choice but to flip The Möbius Book on its head, open the back cover, and begin again.

In the second half of The Möbius Book, a new character appears: Catherine Lacey herself. We learn about how her relationship with her partner of six years ended suddenly; how she was forced to sell her house and split the mortgage; and, ultimately, how she lost herself along the way. “What do you call it when a man emails you from the other room to explain that he met another woman last week and now it’s over?” Lacey asks the reader.

She begins this story by telling us how her marriage came undone: One day, we learn, Lacey’s husband, a writer and professor with a proclivity for anger, ends their relationship in a flash. “The Reason,” as Lacey refers to her ex-husband throughout the story, tells her that she has clearly “stopped loving him” and that the reason they weren’t having “as much sex as he would have liked” is because she was, “most likely, just a lesbian.” Lacey is surprised by these declarations, but she also feels as if she has no agency to argue against them, for “later it became clear—The Reason had the right to explain my feelings to me because he’d spent six years telling me who I was, and what I should want or do.”

For the remainder of this second book, we follow Lacey’s thinking as she becomes unmoored, starves herself thin, and jolts herself into quick-and-hot rebound relationships that leave her feeling “emotionally shrink-wrapped.” That Lacey refers to her estranged partner only as The Reason, while most other figures receive real names or at least monikers, is germane here: It is one signal among others that this book isn’t so much a personal history of a relationship as it is about how a relationship can change one’s sense of reality.

How else should we interpret a book that moves not chronologically or even logically, but betwixt itself? Part of the magic of The Möbius Book is that new metaphors and meanings emerge and come into focus as one reads its two different parts. As one reads book two after completing book one, for example, it becomes clear that Lacey shares much with Edie in the earlier tale.

Once that association has been made, the reader can connect the dots to form a clearer picture of Lacey, how she was raised, and what misdeeds have followed her from one relationship to another. In book one, we learn about a betraying parent who closely resembles Lacey’s father. It is him that she thinks of when she recalls The Reason, who, during their marriage, punches walls so hard he breaks his hand. An enraged father followed by an even angrier husband—such are the patterns of life and fiction.

The Möbius Book, as its title might suggest, is full of these associations: clues from real life that shed light on its metaphors and hints in the fiction that elucidate Lacey’s own past. There is also a lot of talk about feeling guilt even though you haven’t committed a crime; about finding and losing faith; about hearing messages from species who can’t speak any human tongue; and even, at one point, about an exorcism that a friend performs on her in Oaxaca.

None of these supernatural references will surprise her longtime readers: In addition to formal invention, Lacey’s earlier novels abound with allegory, religious trauma, and spirituality. Yet one mystery remains unsolved in The Möbius Book: Amid its shocking, beguiling tales is that pool of blood. While we do eventually learn its likely cause, the explanation is so strange as to muddle our understanding of interpretation itself. But that, too, seems to be intentional. For if most of Lacey’s fiction is about running away from something or someone, in The Möbius Book we also get a study of how ignoring the past nearly always results in loss: not only of one’s tangible identity, but also of one’s coherence, orientation, and sense of meaning.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →In this way, The Möbius Book is reminiscent of work by writers like Sheila Heti, Leslie Jamison, and Maggie Nelson. But in another way, the book is also something novel: While Lacey sets out to write both fiction and memoir tinged with universalisms, she resists combining the two genres explicitly; each has its own separate place in the work. As one of Lacey’s many lovely poetic bromides reads (in this case, taken from a jar of peanut butter): “Separation is natural.”

Separation is natural, but when a heartbroken person searches for connection, she is struggling to fill a void. In the book’s memoiristic section, Lacey tells us about her escapades with various people in various locales. She goes hiking with strangers, considers energy healing, and does “anything I had previously believed myself not to be the type of person to do.” She moves from Chicago to Los Angeles, from Los Angeles to a hotel room in Manhattan, from a beach in Mexico to a cabin in Switzerland, each time not quite finding what she is after.

At one point while she’s in New York City, Lacey takes a trip to the Museum of Modern Art with her friend Avery. Admiring Matisse’s Red Studio, the two women commiserate over how neither of their writing projects is going very well. “Our trouble was a shared one,” Lacey observes. “We were looking for endings, but all we could find was more middle. It was hard, we agreed, to find satisfying conclusions to stories that weren’t exactly stories but rather a set of prompts that resisted completion, a Möbius strip of narrative.”

Most of the author’s platonic and romantic relationships after The Reason amount to nothing permanent, while most of her attempts at closure come to even less. But eventually—or perhaps inevitably—she does find something meaningful. In Mexico, Lacey meets a man named Daniel, with whom she splits a tab of acid. They go to a mutual friend’s house for food, where they are offered a jar of artichokes. Connections compound; separation is not the only natural experience. That summer evening with Daniel turns into months, then seasons, until Lacey finds herself in love with him. On the story’s final page, she asks Daniel a question about their future while they sit in a library. Outside, she sees tourists taking pictures with “out-of-commission payphones.” She is bringing us back to Marie and Edie and some of the unsolved mysteries that opened the book.

Catherine Lacey is much more interested in the questions than the answers, and so the circular nature of The Möbius Book seems fitting: It turns out that the maze she sends us into has no exit and no end. Just like a Möbius strip, we might be sliced down our middles, even split in half. But the bind that holds us together will always stay intact.

Take a stand against Trump and support The Nation!

In this moment of crisis, we need a unified, progressive opposition to Donald Trump.

We’re starting to see one take shape in the streets and at ballot boxes across the country: from New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani’s campaign focused on affordability, to communities protecting their neighbors from ICE, to the senators opposing arms shipments to Israel.

The Democratic Party has an urgent choice to make: Will it embrace a politics that is principled and popular, or will it continue to insist on losing elections with the out-of-touch elites and consultants that got us here?

At The Nation, we know which side we’re on. Every day, we make the case for a more democratic and equal world by championing progressive leaders, lifting up movements fighting for justice, and exposing the oligarchs and corporations profiting at the expense of us all. Our independent journalism informs and empowers progressives across the country and helps bring this politics to new readers ready to join the fight.

We need your help to continue this work. Will you donate to support The Nation’s independent journalism? Every contribution goes to our award-winning reporting, analysis, and commentary.

Thank you for helping us take on Trump and build the just society we know is possible.

Sincerely,

Bhaskar Sunkara

President, The Nation

More from The Nation

The Empty Provocations of “Eddington” The Empty Provocations of “Eddington”

Ari Aster’s farcical western is billed as a send-up of the puerile politics of the Covid years. In reality, it’s a film that seems to have no politics at all.

The Rot at Fort Bragg The Rot at Fort Bragg

Seth Harp exposes how all the death and crime surrounding one military base is not an aberration but representative of the fratricidal impulse of the armed forces at large.

The Revolutionary Politics of “Andor” The Revolutionary Politics of “Andor”

The latest addition to the "Star Wars "series offers an intricate tale of radicalization and its costs.

Billy Wilder’s Battle With the Past Billy Wilder’s Battle With the Past

How the fabled Hollywood director confronted survivor’s guilt, the legacies of the Holocaust, and the paradoxes of Zionism.

The Art and Genius of Lorna Simpson The Art and Genius of Lorna Simpson

A new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art tracks what has changed and what has remained the same in the artist’s work.