Billy Wilder’s Battle With the Past

How the fabled Hollywood director confronted survivor’s guilt, the legacies of the Holocaust, and the paradoxes of Zionism.

Billy Wilder walks down a London street during the 1969 filming of The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes.

(Susan Wood / Getty Images)For 22 months, Hollywood has had no unified voice on the aftermath of October 7. Some knew from day one which side they were on and have not wavered. For others, sympathies for the 1,200 Israeli civilians killed in the attack and the 251 hostages taken by Hamas soon included the tens of thousands of Palestinian civilian casualties, especially the children, who had nothing to do with the attacks.

The debate around Israel’s invasion of Gaza has been distorted by two conflicting and unreliable narratives from Hamas and the Netanyahu government, together with multiple interpretations of words like “genocide,” “Zionism,” “antisemitism,” and phrases like “from the river to the sea” and “globalize the intifada.” Jonathan Glazer’s 2024 Oscar acceptance speech for his Holocaust-themed film Zone of Interest answered those who use Judaism to justify the invasion instead of condemning it, and lent fresh urgency to the claim that the brutal assault was, in fact, a genocide.

Forty-three years ago, another prominent director struggled with many of these same issues—the Austrian émigré Billy Wilder. By 1982, Wilder had six Oscars. The string of films behind them included Ninotchka, The Lost Weekend, Double Indemnity, Sunset Boulevard, Stalag 17, Some Like It Hot, The Apartment, and One, Two, Three. In June 1982, the Israeli invasion of Lebanon troubled him deeply. In pursuit of Yasser Arafat and the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) crossed the border into Lebanon. Their aim was to lay siege to Beirut and track down the leaders of the PLO in order to destroy the organization—the same playbook they’ve used against Hamas in Gaza, albeit under conditions of far more widespread destruction and starvation. The IDF failed in 1982, and in response to the invasion, Hezbollah formed in South Lebanon. Israel still fights Hezbollah to this day.

At 75, Wilder did not know it, but he had made his last movie, 1981’s Buddy, Buddy. Written with his longtime collaborator IAL “Izzy” Diamond and starring longtime Wilder favorites Walter Matthau and Jack Lemmon, it landed as a commercial and critical flop. It was one in a long string of late-career disappointments for Wilder and Diamond. Before that, they made Fedora (1978), The Front Page (1974), and The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970). Wilder’s last films vary in quality, but few found an audience, so he regarded them as failures, too. “He himself said, ‘I’m not making movies for six people in Bel Air,’” says Jonathan Coe, whose novel Mr. Wilder & Me on the making of Fedora is in development with Stephen Frears attached to direct and Christoph Waltz playing Wilder. “He didn’t see the point of films like that. There was no distinction for Wilder between commercial success and artistic success, I don’t think. If a film flopped commercially, then he wouldn’t talk about it. He wasn’t interested in it anymore. He accepted the judgment of the marketplace, absolutely.”

You couldn’t tell that Wilder had hit the end of his professional life if you’d seen him holding court with Kirk Douglas, Sidney Poitier, or Gregory Peck at Wolfgang Puck’s trendy new restaurant, Spago. But his streak of hits was over. “What he had been doing had worked well the majority of the time for 50 years. That’s hard to turn down and admit defeat or that they’ve passed you by,” says Diamond’s son, writer Paul Diamond. “America had passed them by.”

Wilder still went to the Beverly Hills office he shared with Izzy Diamond every morning, but Diamond showed up less and less. He later grew ill, and died in 1988 at 68. With no work, Wilder met more and more with journalists and filmmakers who sought out the wisdom of one of the last auteurs of Hollywood’s golden age. “There’s a difference between a production office and a salon,” Paul Diamond says. “He was running a salon.”

By 1982, Wilder had spent nearly half a century in Los Angeles. He had fled Germany in 1933 for Paris. Already a screenwriter in Berlin, he saw Hitler named chancellor and got nervous. A month later, he cleaned out his bank account and bought a one-way ticket to Paris. From Paris, he sold a story to a German director he knew at Columbia. It got Wilder a work visa and a ticket to Hollywood that saved his life.

From his family, only his older brother, Wilhelm, got out. The lesser-known Wilder, Wilhelm produced low-budget horror schlock like Manfish and The Man Without a Body under the grandiose screen credit, “W. Lee Wilder.” As for the rest of the family, the far more accomplished Wilder known simply as “Billy” spent decades wracked with “fury, tears, reproaches,” as he told Michiko Kakutani, over his failure to get them out of Vienna before the 1938 Anschluss. “I left the day after the Reichstag fire, and I left my parents in Vienna,” he said. “What is done is done, and cannot be undone.” His mother, stepfather, and grandmother all stayed behind. “The optimists died in Auschwitz,” he would say later. “The pessimists have pools in Beverly Hills.”

In early 1982, at 77, Wilhelm died. That June, Israeli journalist Benny Landau stopped by the office to interview Wilder. Landau surprised Wilder by asking him about Israel and the ongoing invasion of Lebanon. It was not a Six-Day War, but a conflict that dragged on for months without any victory for Israel to claim. When you’re Billy Wilder, you expect questions about Marilyn Monroe, not Menachem Begin—but Wilder offered a chastened view of the war anyway. “I don’t feel good about [the siege on] Beirut,” Wilder told Landau, “but my heart is with the soldiers.”

Wilder had been an ardent Zionist since the 1920s, but as the Palestinian-Israeli conflict entered a new decade, he looked on with dismay at yet another front opening up. “I would have liked someone to explain to me,” he asked Landau, “how the problem will be solved if we take the cancer from Beirut and transfer it to Damascus or Riyadh.… When you talk to the average American, or to your non-Jewish wife, you feel disappointment, you sense their apprehension that the state, which always looked brilliant and sophisticated, is sinking into some kind of fanatical aggression, a cycle of an eye for an eye.” Nor did Wilder feel that Israel’s long record of success with targeted assassinations would reverse the cycle. “I don’t believe that the elimination of [Yasser] Arafat will solve the problem. In [the Palestinians’] ranks fight kids who were taught, since they were two years old, that they should destroy the State of Israel. This war [in Lebanon] is turning into a fanatic, religious war.”

Forty-three years later, as Israel reoccupies Gaza with a siege on Gaza City, and religious fanatics in Washington and Tel Aviv argue that God deeded the entire West Bank to Israel, it’s hard to argue with Wilder’s glum appraisal. As Billy Wilder looked for a final film, his thoughts turned increasingly to his dark past.

Born in Sucha Beskidzka, Austria-Hungary (now in Poland) in 1906, Wilder moved with his family to Vienna as a child. His mother had visited America once. She nicknamed him “Billie” after Buffalo Bill. He grew up an outsider in Vienna, Jewish and Polish, and spent his high-school years watching Douglas Fairbanks silents and westerns at the nearby Rotenturm Kino and falling in love with American pop culture and jazz. Rather than go to college, he chose journalism, and got freelance work at a Vienna scandal sheet. He chased local and visiting celebrities. When American bandleader Paul Whiteman toured Europe, he stopped in Vienna to visit for pleasure, not to perform. The young Wilder charmed him, as he could anyone, and upon seeing Wilder’s disappointment at missing the band’s Berlin show, Whiteman invited him along to Berlin as his guest. Wilder left Vienna behind for a very long time.

As talented a hustler as he was a writer, Wilder soon got some freelance reporting work, but also moonlighted as a dancer and gigolo at the Hotel Eden—an experience that he turned into a series of articles for B.Z. em Mittag. For the same magazine, he reviewed a documentary, Frühling in Palastina or “Springtime for Palestine.” “Twenty-five years ago a barren desert with noxious swamps,” he gushed of early Tel Aviv, “today a city with forty-five thousand residents, lovely wide streets, handsome garden villas, schools, sanatoriums, factories, the future seaside resort of the Orient—Tel Aviv.”

Neither the film nor his review mentions rising tensions between displaced Arab residents and the new ones in the region. For Wilder in the late 1920s, a Jewish life outside Europe, whether in idealized American movies or a utopian view of Tel Aviv, was increasingly attractive. Weimar Berlin proved an exciting, wide-open city for a talent like his and by 1928 he was ghostwriting movies, but he also nervously eyed the Nazis gaining seats in the Reichstag. That year he landed his first screen credit on Hell of a Reporter or Der Teufelsreporter (1928). It tells the story if a hustling young Berlin journalist who saves a group of American girls from gangsters. Those who knew Wilder said he already played the part of an American. He wore his hat cocked to the side, let his cigarettes dangle in the corner of his mouth, and kept his hands deep in the pockets of his long overcoats. “I knew a few Americans in Berlin,” he recalled, “and I tried to imitate their style of dressing and talking.”

Most likely, he had also been watching the success of German directors like Lubitsch, F.W. Murnau, and Josef von Sternberg in the United States, and then Marlene Dietrich’s emergence as an émigré film star. By February 1933, he took that train to Paris and made it to America. Two touch-and-go years in Hollywood later, Wilder had established himself as a screenwriter and lived at the Chateau Marmont. He returned to Vienna in 1935, but he could see he made old friends uncomfortable. Was it his success? Did they not want to be seen associating with a Jew? He begged his mother and stepfather to leave. They downplayed the threat of Hitlerism in Austria, refusing to believe it could take hold in sophisticated Vienna. Wilder’s stepfather wasn’t a 29-year-old with prospects in Hollywood; he was a middle-aged man who ran a string of cafés. They stayed. For the rest of his life, Wilder blamed himself for not somehow convincing them to leave.

Back in the States, Wilder’s career took off with a new writing partner, Charles Brackett. By 1939, they won Academy Award nominations for writing the Greta Garbo vehicle Ninotchka for Ernst Lubitsch. Wilder’s agent Paul Kohner organized a European Emergency Fund with German and Jewish expats like Dietrich and Wilder to get people out. Obviously, rescuing his mother from Europe was on his mind. At MGM, he worked on Heil, Darling, an unproduced treatment about an American reporter of suspected non-Aryan heritage trying to marry a wealthy German woman so she can move her money out of the country. At Paramount, he developed a never-produced project called Polonaise meant to feature William Holden as a Notre Dame football star trying to get his grandmother out of Poland.

Wilder did not return to Germany until 1945, when he worked for the US government’s Office of War Information (OWI). For the OWI, he produced and edited Death Mills, a documentary on the camps meant to be shown to Germans. He sat through the endless horror show of footage, losing himself in the images, looking for any sign of his mother. His work also included the denazification of the German film industry—banning those who worked at the Nazi-owned UFA studio, churning out the worst of Joseph Goebbels’s propaganda. It’s a moment Jonathan Coe’s Mr. Wilder & Me dramatizes with a perfect Wilderian scene, presented in the format of a screenplay. Wilder interviewed actor Werner Krauss, who specialized in antisemitic caricatures for films like Jew Süss:

BILLY

You are applying, according to this, to make a performance of the Passion Play in Oberammergau later this year. You intend to take the role of Jesus Christ—is that right?KRAUSS

Yes.BILLY

Well, I don’t see that there will be any problem with that.KRAUSS is visibly relieved. He is about to say thank you.

BILLY (CONT’D)

On one condition, that is. When you come to the crucifixion scene,

I want you to use real nails.

Certainly, Wilder rooted out all the hardcore Nazis he could, but his interviews undoubtedly exposed him to those who did what they had to do to stay alive. That experience had a surprising influence on his postwar Berlin film, A Foreign Affair. “What’s remarkable about that film is here he had his mother and other relatives who died in Auschwitz,” says film historian Kevin Lally, author of the biography Wilder Times, “and that film is very compassionate toward the German people. The scenes of people struggling and just getting by at the black market… you’ve got these aerial shots of bombed out Berlin. The Marlene Dietrich character consorts with Hitler, yet she’s still so charismatic. It’s just amazing to me that he had all this pain from the suffering and death of his relatives yet he was able to make a film that showed such compassion to the Germans.”

“There’s a decent chance that Wilder did his background ‘research’ while serving in the OWI. I don’t think that’s a big leap,” says Noah Isenberg, who edited Billy Wilder on Assignment: Dispatches from Weimar Berlin and Interwar Vienna and is at work on a Wilder biography for Yale’s Jewish Lives series. “He made a clear distinction between the political opportunist à la Erika von Schlütow in A Foreign Affair and the heel-clicking variety à la Otto von Scherbach in Stalag 17 or even the mashup in Schlemmer from One, Two, Three.”

Moral compromise is the driving idea behind A Foreign Affair, which was released in 1948. In it, Marlene Dietrich plays cabaret singer Erika von Schlütow. She’s sleeping with an American officer who can get her food or even just a mattress to sleep on when US intelligence spots her in a newsreel consorting with top Nazis. They use her and her American boyfriend as bait to draw her jealous former SS boyfriend out of hiding. When he emerges, they kill him in a shootout at the rathskeller where she sings. They arrest her, but Wilder and Brackett give Dietrich a signature exit. As the MPs lead her out, she flashes some leg, and asks them to stop at her apartment for a few things to take to jail. Her sultry “C’mon boys” lets us know Erika von Schlütow will survive no matter who rules Germany.

Wilder populates his movies with the compromised. They’re sell-outs, cynics, and manipulators, but they often have a rusty moral compass that still works. Sergeant J.J. Sefton (William Holden), in Stalag 17, survives Colonel Oberst von Scherbach’s (Otto Preminger) prison camp by trading with the Germans for food and favors and in turn runs a black market of his own to gouge his fellow POWs, relying on the same amoral survival instincts that guided Erika von Schlütow. But it’s Frank Price (Peter Graves), the Nazi spy in the camp, who earns Sefton’s hatred after he gets several American POWs killed trying to escape. Like von Schlütow, Sefton’s happy to get a Nazi killed if he gets the chance.

Still, Wilder’s hard feelings about Nazis came to the fore in 1954 when a mid-level Paramount executive informed him that the German print of Stalag 17 would make the barracks spy Polish to please the German distributors. As Wilder recalled, “I just said: ‘Fuck you, gentlemen. Haven’t you got any shame? You ask me, who lost his family in Auschwitz, to do a mistake like this? Unless somebody apologizes, forget about my contract. Good-bye, Paramount. Nobody apologized, and I left Paramount.” (Only in 2011—nine years after Wilder’s death—was it learned that his mother and stepfather died in Plaszow and Belzec, respectively, and his grandmother in the Nowy Targ ghetto.)

Perhaps his work on Death Mills represented all Wilder needed to say about the Holocaust for the time being. In the years leading up to A Foreign Affair, his mind turned back to Zionism and British Palestine. In 1946, Brackett’s journals give a glimpse at what they planned. They hoped to cast James Mason as a gunrunner—a non-Zionist British Jew—who sold guns to both sides, Palestinian Arabs and Palestinian Jews, “until he sees the light” Brackett’s journals tells us, and only sells to the Zionists. But his conversion comes too late, and he’s killed by an Arab fighter using one of his guns.

Wilder planned a research trip to Palestine in 1948, but the British wouldn’t allow him in during that incredibly volatile period. After Israel’s founding, Paramount let Wilder know once and for all that the studio had no interest in the project. Wilder’s support for Israel stayed strong, via donations and his presence at the 1967 Rally for the Survival of Israel after the Six-Day War. In Avanti! (1972), his script mentions Israel in a comic exchange between a State Department official named J.J. Blodgett and a hotelier seeking his opinion on taking a job in Damascus. Blodgett replies that with “the military posture of the Arabs stiffening and the first-strike capabilities of the Israelis at its peak, the whole place is a powder keg that could blow up in your face any second. My advice is, forget Damascus.” When the man says that his only other job offer is the Sheraton in New York, Blodgett replies, “Take the one in Damascus.” By the 1982 siege of Beirut, Israel had signed the Camp David Accords with Egypt and had evolved into one of the region’s key military powers.

In 1982, MGM/UA hired Wilder—not to direct, but to mentor its younger filmmakers on projects. “When I was making E.T. and Poltergeist at MGM, Billy was a consultant there,” Steven Spielberg has said. “Billy felt he was wasting his life. We would have lunch often in the commissary, and Billy would say, ‘I just cannot get a film off the ground anymore. Whatever worked for me for 30 years is not working anymore.’”

And then the honors started rolling in: the ones that tell you the world thinks you are a very, very old man. In 1982, Wilder received a Lincoln Center Tribute and a 35-film retrospective. In 1984, the Directors Guild of America presented him with its Lifetime Achievement Award. In 1986, the American Film Institute presented him its AFI Lifetime Achievement Award. In 1988, the Academy capped off the six Oscars he already had with its Irving G. Thalberg Award. In 1990, President George H.W. Bush awarded him a Kennedy Center honor. Wilder accepted them graciously, but with a healthy dose of side-eye. “One more marker to the grave,” he called them.

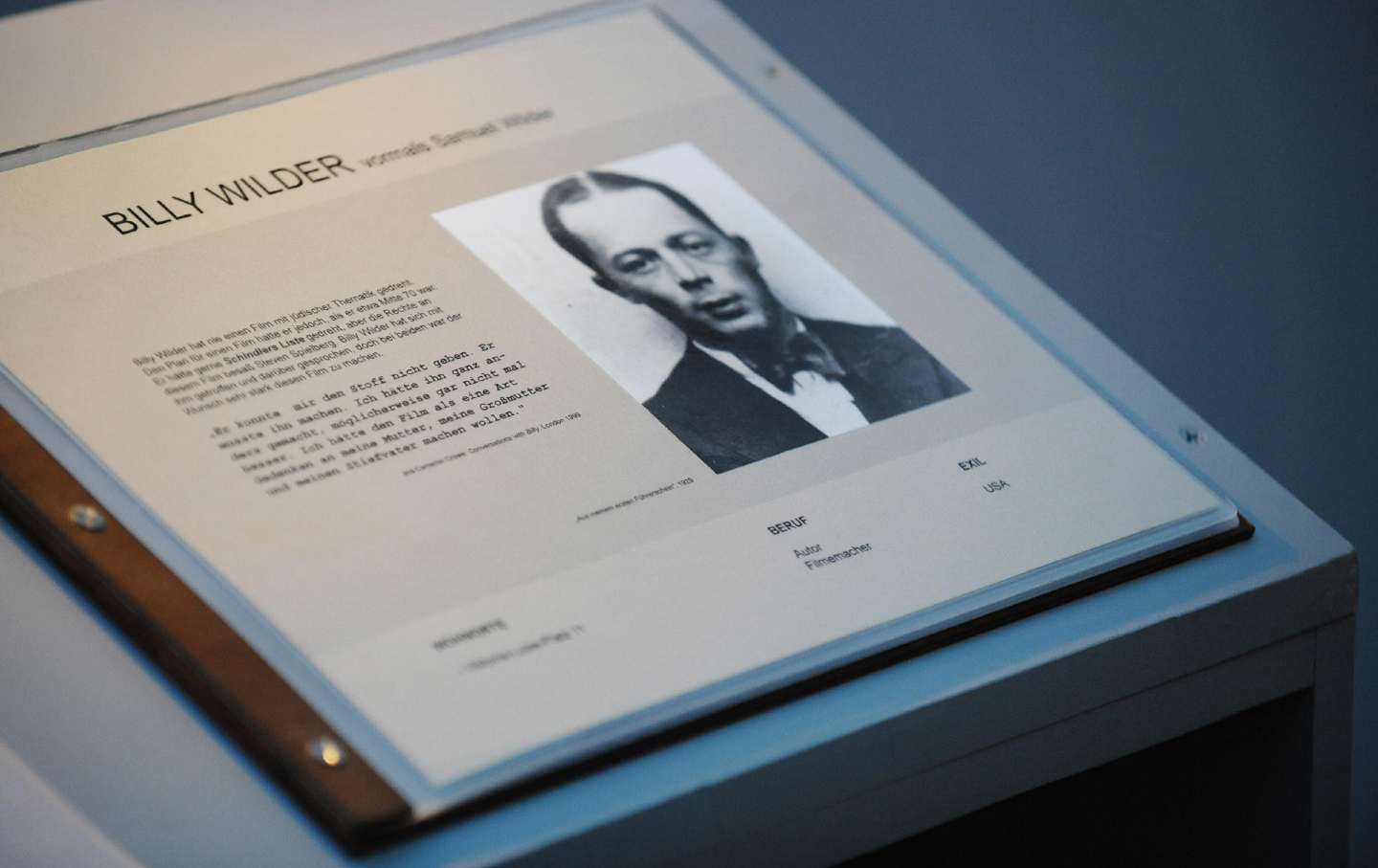

In 1993, Wilder found the story he knew should be his last film. He read Thomas Keneally’s Schindler’s Ark, a novel that said everything he wanted to say, and with an exquisitely Wilderian character at its center. Keneally based it on factory owner Oskar Schindler, a Nazi-aligned businessman whose champagne-soaked parties won him a factory formerly owned by a Polish Jew and the lucrative German contracts that came with it. To keep the firm running, he found he needed the factory’s Jewish employees. First out of necessity, then a growing conscience, Schindler used his position to keep his Jewish factory workers out of the camps. Schindler’s conversion of conscience—the moment when he “saw the light,” as Brackett wrote of their Zionist gunrunner in the mid-1940s—was a natural subject for Wilder,

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →When he looked into the film rights for the novel, he found that Universal had acquired them for Spielberg a decade earlier, and Spielberg still had not made the film. “He called me at the office and said, ‘I need to see you, it’s very important,’” Spielberg recalled. “I said, ‘OK, I’ll come over to your house.’ He said, ‘No, I need to come to you, because I’m going to ask you for something.’ So he came over to Amblin and up to my office, and he said, ‘I just read a book and found out you own it, Schindler’s List [sic]. This is my experience before I came to America. I lost everyone over there. I need to tell this story, and I hear you own the rights. Will you let me direct this and you can produce it with me?’ And I didn’t know what to say, except to tell him the truth. I said, ‘Billy, I’m leaving for Krakow in three weeks. The whole film’s been cast. All the crew’s been hired. I start shooting at the end of February.’ Billy couldn’t speak, and then I couldn’t speak, and I just reached my hand out and Billy took my hand.”

All Wilder could do now was wait for the movie. Until then, more honors. That year, President Bill Clinton nominated him for the National Medal of the Arts, and the Berlin Film Festival awarded him its Golden Bear Lifetime Achievement Award. One honor that left him cold was a request from Austrian Chancellor Franz Vranitzky to return to Vienna. He turned it down. Wilder had been back in 1952 with his wife, Audrey, William Holden, and Holden’s wife, Brenda Marshall. They visited the mountain spas at Bad Gastein and then Vienna, but Wilder saw that Austria remained indifferent to its recent past and to Wilder alike. In 1958, he returned with Charles Laughton and Tyrone Power after promoting Witness for the Prosecution (1957) in Europe. Vienna still appealed to Wilder as a city of museums and restaurants, but he felt no affinity for the Austrians.

In September 1993, Kevin Lally requested an interview with Wilder for Wilder Times. Word got back to him through Wilder’s agent. Wilder had said, “If Mr. Rabin can shake hands with Mr. Arafat, I can talk to Mr. Lally.” This was of course a joke, since Wilder had no reason not to talk to Lally, and after meeting Lally for their initial interview, granted him several more hours. But the throwaway line does suggest that Wilder actually verged on optimism over the Oslo Accords negotiations, which began when Rabin and Arafat shook hands at the White House. Here was a glimmer of hope that the fanaticism of the 1980s might end. (That hope proved tragically short-lived when Rabin was assassinated by an Israeli extremist in 1995.)

On September 17, Wilder and Lally had their first meeting. During the interview, an Austrian official called to plead once more with Wilder to return to his homeland. With Wilder accepting the Berlin award, perhaps this year he would finally come to Vienna as an honored guest. When Wilder got off the phone, he was direct and blunt. “Let us not forget that Mr. Hitler was Austrian,” Wilder told Lally. “As they say now, the Austrians are absolute magicians—they have now convinced the world that Beethoven was an Austrian and Hitler was a German. I always get into terrible fights with the newspapermen, because I remember my days in school. I remember the attitudes.… I hate to go to Vienna. I guarantee you there will be a thousand people outside the hotel screaming, ‘Get the Jew out.’”

Wilder felt the harms of the past deeply, but he usually hid them under a cavalier quip. For once, the mask of the jaded cynic had slipped completely. He composed himself and said, “Don’t write that, please.” Lally honored Wilder’s wishes during his lifetime and, like Benny Landau’s Haaretz interview, it only appeared posthumously. But as Wilder’s Berlin visit grew closer, Vranitzky extended a personal invitation, and surprisingly, Wilder said yes.

What changed his mind? First, Wilder received a call from Austrian filmmaker Wolfgang Glück, a friend he trusted, who pleaded with him to go. Second, in November, Schindler’s List opened in Los Angeles. Spielberg’s screenwriter, Steven Zallian, closed the movie with a scene featuring Schindler alongside the 1,100 Jews he saved, but still wracked with survivor’s guilt. “I could have saved more,” he said. “I could have saved more.”

Wilder saw Schindler’s List at Laemmle’s Music Hall in Beverly Hills. He recalled leaving the theater and not speaking for three hours. He saw it two more times, and planned a fourth. If Rabin and Arafat could shake hands, Billy Wilder could go to Vienna.

In May 1996, Wilder accepted his latest lifetime achievement award in Berlin. While there, he also took out an ad in a German magazine, Süddeutchen Zeitung Magazin. The ad was about Schindler’s List, but aimed specifically at the Holocaust denial movement. In 1993, Deborah Lipstadt published Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory, which offered a scathing appraisal of the professional Holocaust denier David Irving. Wilder biographer Ed Sikov notes that he chose S-Z Magazin because it was based in conservative southern Germany—the place where the Nazi movement first took hold.

“The most important function of this movie is this,” Wilder wrote in the ad, in reference to Schindler’s List: “It manifests for all time that these unbelievable cruelties really happened. We need not forget that. With each year dust lays itself on this history; it is pushed away, forgotten. The young people, growing up today without the awareness of it, are already doubting that such a horror really could happen in the cultivated country of Goethe. ‘The Auschwitz myth.’ Nonsense, more and more people are saying concentration camps, gas chambers, all that exists only in a Jewish fantasy. I venture to ask in each case: if the concentration camps and the gas chambers were all imaginary, then please tell me—where is my mother? Where can I find her?”

Just as he made Death Mills with the intention of having every German see it, Wilder now wanted all Germans and Austrians to face up to Holocaust denialism. Then he went to Vienna.

When Wilder got there, whatever anxiety he had evaporated. Unlike previous visits, there was no indifference, let alone antisemitic mobs outside his hotel. He was welcomed at the airport by the chancellor and taken to his old apartment building, where an official government marker now recognized the Wilder family’s former home. Austria held a state dinner in his honor, and Wilder was visibly moved by the chancellor’s toast, where he shared the hope that Wilder would see “a new Austria.”

Wilder would never get over the loss of his family, but he eventually found a way past some of the anger. If the effort to overcome historical resentments didn’t last in the Middle East, it did with Wilder. The characters in his movies who can’t get over the past, like Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard, or the title character in Fedora, are the saddest of all. Billy Wilder wasn’t one of them.

Take a stand against Trump and support The Nation!

In this moment of crisis, we need a unified, progressive opposition to Donald Trump.

We’re starting to see one take shape in the streets and at ballot boxes across the country: from New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani’s campaign focused on affordability, to communities protecting their neighbors from ICE, to the senators opposing arms shipments to Israel.

The Democratic Party has an urgent choice to make: Will it embrace a politics that is principled and popular, or will it continue to insist on losing elections with the out-of-touch elites and consultants that got us here?

At The Nation, we know which side we’re on. Every day, we make the case for a more democratic and equal world by championing progressive leaders, lifting up movements fighting for justice, and exposing the oligarchs and corporations profiting at the expense of us all. Our independent journalism informs and empowers progressives across the country and helps bring this politics to new readers ready to join the fight.

We need your help to continue this work. Will you donate to support The Nation’s independent journalism? Every contribution goes to our award-winning reporting, analysis, and commentary.

Thank you for helping us take on Trump and build the just society we know is possible.

Sincerely,

Bhaskar Sunkara

President, The Nation

More from The Nation

The Empty Provocations of “Eddington” The Empty Provocations of “Eddington”

Ari Aster’s farcical western is billed as a send-up of the puerile politics of the Covid years. In reality, it’s a film that seems to have no politics at all.

The Rot at Fort Bragg The Rot at Fort Bragg

Seth Harp exposes how all the death and crime surrounding one military base is not an aberration but representative of the fratricidal impulse of the armed forces at large.

The Revolutionary Politics of “Andor” The Revolutionary Politics of “Andor”

The latest addition to the "Star Wars "series offers an intricate tale of radicalization and its costs.

The Art and Genius of Lorna Simpson The Art and Genius of Lorna Simpson

A new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art tracks what has changed and what has remained the same in the artist’s work.

Catherine Lacey’s Missed Connections Catherine Lacey’s Missed Connections

In her most personal work, "The Möbius Book", Lacey uses a devastating moment of heartbreak to ruminate on the messy intersections between life and writing.