Why We Must Keep Talking About Abortion Pills

As part of a delegation to Brazil, I saw how our countries’ respective struggles to maintain and expand reproductive justice are really part of the same fight.

The author, Regina Mahone, left, and Rio de Janeiro-based journalist Nicole Froio.

(Kisha Bari)Brasília, Brazil—We packed ourselves into a meeting room at the back of the Socialism and Freedom Party (known as PSOL) office in the National Congress building in Brasília on May 14. The bird-shaped capital of Brazil was developed in the 1950s as a modern, futuristic city, but inside the legislative building are standard government meeting spaces, with cubicle walls and drab, windowless halls.

We took our seats at the big conference table or on one of the folding chairs located along the sides. Lunch was served—an assortment of breads, including the staple pão de queijo; salads; fresh juice; and Brazilian carrot cake, which was fluffy (nothing like the traditional US version) and delicious.

Minutes later, Congresswoman Célia Xakriabá, wearing a feather headdress, joined the meeting via Zoom to welcome our delegation of US policymakers and journalists who had come together to learn about abortion and maternal health in Brazil and to share strategies for improving access to care in hostile governments. Xakriabá of the Xakriabá Indigenous people, from the Cerrado biome, is the federal deputy of the PSOL, and she opened the discussion by acknowledging the legislators in the delegation—all women of color—saying, in Portuguese, “It’s good to see young women here, because we know they are the ones to innovate politics.” The congresswoman invited the delegates to return to Brazil for COP30 in November, where her commission will discuss reproductive rights, gender-based violence, and environmental racism: “There’s no climate justice without women.”

Xakriabá wasted no time before explaining how these issues overlap in Brazil. Even before the conservative members of Brazil’s legislature approved a “Poison Package” that would weaken the country’s already loose regulation of pesticide use, human rights groups had warned about the mounting health risks in agricultural areas. Whole regions can be contaminated by “pesticide drift”—when wind blows pesticides beyond the intended fields—affecting farming communities, rural schools, and Indigenous and Afro-Brazilian settlements.

Pesticide contamination can have devastating consequences for children and pregnant people. One 2024 study found that in the major agribusiness cities in Mato Grosso, which is one of the largest exporters of soybeans and cattle in the country, the risk of congenital anomalies was 20 percent higher than in non-farming regions, while the risk of fetal death was 30 percent higher. And tragically, the risk of dying before birth was 73 percent higher in parts of Rio Grande do Sul, where Dialogue Earth has reported that farmers have sued pesticide manufacturers and state and local governments to ban spraying pesticides by plane.

For a number of women in these communities, explained Xakriabá, they are seeking abortions “not because they chose. It’s because of the pesticide [contamination] rates.” She said that women and children become contaminated with mercury because of illegal mining and heavy metals, and “a lot of women don’t want to get pregnant because their children will be born with disease or malformations.”

Sexual violence is also rampant. Congresswoman Erika Kokay of the Workers Party, who was seated at the table and spoke to the delegation after Xakriabá, noted that there is a rape every six minutes in Brazil. More than 60 percent of those cases, nationally, involve children 13 years old or younger. Keka Bagno, the coordinator of the Human Rights Commission in the Legislative Chamber of the Federal District, who sat alongside Kokay at the front of the room, pointed out that trans people are among those being killed by this violence.

In Brazil, patients are permitted legal abortions only after qualifying for one of the three exceptions—the pregnancy was the result of rape or incest, the pregnant person’s life is at risk, or the fetus has been diagnosed with anencephaly (a fatal birth defect)—but then they also have to access that care at a public hospital. Qualifying abortions are covered under the country’s universal health care program, the Unified Health System. However, public facilities that offer abortion care (60 percent of all hospitals, according to Dr. Andréia Regina Aráujo, who spoke to the delegation at the Hospital Materno Infantil de Brasília) tend to be in densely populated areas that are often difficult for people in rural communities to reach.

There is a case before the Brazilian Supreme Court that could decriminalize abortion during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, but the court has postponed debating the issue, with no new date set. And although leftist leader Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva assumed the presidency after defeating the far-right incumbent Jair Bolsonaro in 2022, conservatives in the federal legislature are pushing a bill that would treat abortion after 22 weeks as a homicide.

“Our reality must be changed,” Kokay said, speaking in Portuguese. Not only is the status quo under threat, she explained, but conservative lawmakers “want to go back.” They have presented many proposals, she said, including personhood legislation to define life as beginning at conception, “which would criminalize any interruption of pregnancy.” They are also trying to take away emergency contraception. “Every day it’s something else,” she said. “We fight every day not to go backward.”

The lack of access to legal abortion care pushes Brazilians to seek abortions through illegal means, with many obtaining Cytotec, or misoprostol, from drug traffickers. As even the World Health Organization has noted, the pills are safe to use when terminating a pregnancy, but when patients buy the pills on the black market and, as local providers explained to the delegation, do not receive enough of them to complete the process—the misoprostol-only regimen can require up to 12 pills, four at a time in three doses—complications may arise, contributing to the country’s maternal health crisis.

Brazil’s high maternal mortality rate has declined in recent years, in large part due to improvements in prenatal and obstetric care. In 2011, the United Nations’ Committee on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) condemned Brazil for its treatment of Alyne da Silva Pimentel. The 28-year-old Afro-Brazilian died in 2002 after being sent home without receiving care for pregnancy complications that could have saved her life. CEDAW made several recommendations to Brazil to improve the quality of reproductive health care and reduce preventable deaths, such as through the creation of maternal mortality committees. And the country has made strides since Pimentel’s death, but the maternal mortality rate for Afro-Brazilians remains more than double the rates of white women.

Abortion care is a crucial part of the spectrum of reproductive health care, which includes pregnancy prevention, termination, and labor and delivery. By making abortions inaccessible, lawmakers endanger those most unable to access care in a health crisis, whether they had planned to end the pregnancy or carry it to full term. Abortion pills, for example, are used to manage postpartum bleeding—a leading cause of death in the United States and around the world. But when providers need to clear legal hoops before they can give their patient a dose, healthcare suffers. Julia Piazza, a Brazilian lawyer and member of the Feminist Collective on Sexuality and Health, told us, “There are some advocates who say the medication is in jail. Not just for abortions but for it to be used in different cases when they are necessary.”

This was a shock to many in delegation, because it was the Brazilians who discovered that misoprostol could bring back their periods.

Brazilians have used a variety of abortion methods over the years. As Renee Bracey Sherman and I document in our book, Liberating Abortion, midwives would perform abortions using a rubber tube (called a sondas)—or a papaya tree stem with an injection of an acid. Or people would seek out herbal methods, using local plants such as Arruda to induce an abortion.

Misoprostol became available in Brazil in the late 1980s, and was first prescribed as a treatment for gastric ulcers. Thanks to the ingenuity of drugstore vendors and people of color in favelas, who would tell the community pharmacists which medications worked best, word spread that misoprostol worked better than others, and drug stores would sell the pills without a prescription to get around the country’s strict abortion laws. But the medication became so popular that misinformation about its use began to spread, and in 1991, the Ministry of Health banned the pills unless they were being sold for ulcers. Today, under the country’s restrictive laws, misoprostol can be dispersed for medication abortions only in public hospitals.

Brazilians continue to access misoprostol through legal and illegal means, but the propaganda about medication abortions continues, thanks to the country’s anti-abortion movement that is heavily influenced by, or in some cases even backed by, the same organizations operating in the United States, as Garnet Henderson reported for Rewire News Group.

The US government has also contributed to the devastating conditions in Brazil and other parts of the Global South, such as through the government’s support of far-right leaders, including Bolsonaro and Argentine President Javier Milei. Now, as the Trump administration eliminates global programs like USAID, the United States is putting local climate and health programs at risk, exacerbating the issues the Brazilian legislators raised during our meeting. One USAID-backed program supports efforts of the Amazon-based Roraima Indigenous Council to adapt to climate change by improving family farming and income generation for women. Labor conditions, as is clear from the pesticide contamination in agricultural communities, can exacerbate health risks, not to mention the ability to parent one’s child. Xakriabá told us, “Sometimes women see their bosses more than their child. Sometimes they don’t have the right to go to the bathroom, which is especially a problem when they are menstruating.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →In hosting this delegation—their fifth one in Latin America—the Women’s Equality Center (WEC) and State Innovation Exchange are working to build bridges between US lawmakers and legislators and reproductive health advocates in the Global South so that they can all “become more effective in how we fight back,” said WEC’s executive director Paula Avila-Guillen.

Given how dire the situation is becoming in the United States and the parallels in Brazil—which had its own January 6–style capitol riot on January 8, 2023—it’s difficult to feel inspired. What’s happening is devastating, and it’s being meted out by our government officials. As we were meeting with Brazilian leaders, we heard the news of a pregnant woman in Georgia who had been declared brain-dead in February but was still on mechanical support due to the state’s abortion ban—despite the fact that, as noted bioethicists told the Associated Press, disconnecting her from the machines that were keeping her alive would not constitute an abortion. Meanwhile, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. had ordered the FDA to review mifepristone, the first pill used in medication abortions, in light of highly flawed “new data” that the anti-abortion organization Ethics and Public Policy Center self-published to fuel the Trump administration’s crusade against the wildly popular and overwhelmingly safe abortion method. The United States is going backward.

I asked Avila-Guillen about this. She told me about the first Latin American conference she attended after the Dobbs decision was leaked, where after some pushing the organizers included a panel on Roe. During the panel, the Latin American participants were surprised to learn about the Dobbs ruling, she said, “but they also were surprised to understand the fall of Roe was just the culmination of a bigger plan.” For many of these activists, they did not know that people in the United States, disproportionately people of color, had struggled to get the care they needed even before Roe fell.

“I remember somebody said, ‘We have fought United States imperialism for so long that we forget that their government is not their people.’ And that was a very deep moment for me—for them and for us,” she said.

Since the Dobbs decision three years ago, Avila-Guillen has witnessed organizers work to “build bigger bridges, build a lot more connections, and start sending messages of the resistance, to say, ‘Look, you think things are bad right now? We have been there before, and we have found ways to survive, ways to provide abortion care, ways to fight authoritarianism, and ways to organize.’” That solidarity is what inspires her. “For people who feel that their government’s policies [are the result of US foreign meddling]—they are able to put that aside, and say, ‘This isn’t about those in power, this is about the people. And we the people need to support each other.’”

While the Brazilian legislators elevate these important reproductive justice issues in Congress and prepare to do so in their commission at COP30 later this year, local leaders and advocates are working to provide their communities with the information they need.

AzMina, a digital magazine based in São Paulo, advances human rights and reproductive freedom by developing content that can shift the public conversation around abortion. As journalist and director of audiovisual at AzMina Nathália Cariatti explained to the delegation, much of the mainstream media coverage in Brazil gives more credibility to conservative leaders than to patients and healthcare providers, uses images that misrepresent abortion, and deploys language that pushes a specific narrative. Journalists will often use the word “baby” instead of “embryo” or “fetus” and refer to pregnant patients as “mothers,” even though not everyone who is pregnant will carry their pregnancy to term, a pregnancy might not be wanted, and not everyone who is pregnant identifies as a woman.

As a counter to this anti-abortion rhetoric, AzMina covers abortion as a healthcare issue. “We do a lot of stories thinking about how we can inform people who are looking for abortion, understanding that these people [are often] desperate and…will google about this or look for the information on social media,” Cariatti told the delegation. People will continue to seek out abortions, and it’s essential for them to have accurate information, especially when those who are entitled to legal abortions are being denied the procedure because clinicians or patients are uninformed about the law or because of religious dogma.

We also met with the Rio de Janeiro–based reproductive justice organization Criola, who told us about their work raising awareness and empowering Afro-Brazilians. Criola’s founder, Lucia Maria Xavier de Castro, explained to me that Afro-Brazilians who become pregnant often lack the community support and resources that they need, whether they decide to keep the pregnancy or seek an abortion, which is why the organization has worked under a reproductive justice framework since its founding in 1992.

Criola works to combat the “patriarchal cisheteronormative racism” at the root of this crisis facing Black youth and adults, both cis and trans, through community meetings, conversation circles, education materials, and research. “What we offer, with a lot of care, is more information so that [Black women] can understand that this is not personal and happens to other women as well, and that she has to seek services that are safe for her, because if not, the chances of dying are enormous,” she said through a translator. Criola informs Black pregnant people “so that they understand what is at stake when they make these decisions, what the problems are that they are going to face, and how they can solve the problems from their position.”

Beyond addressing stigma and misinformation in the media and organizing communities and neighbors to protect one another, advocates are working at the national level to improve care. The Collective of Nurses, Midwives, and Obstetricians for the Right to Decide formed one year ago to steward best practices among those caring for abortion patients and improve the codes governing their work so that they are patient-centered. Like advocates in US states with abortion bans, the collective recognizes that it’s crucial to improve not only access to abortion but also the structures of the care system that often prevent providers from meeting the needs of their communities.

Back at the National Congress building, our last stop before leaving was the Plenary of the Federal Senate, where the legislative body meets to debate legislation like the “Poison Package” and the bill seeking to treat later abortions like murder. Much like the US Capitol, the possibility for regression or progress in this one dome-shaped room felt heavy. Ky Polanco of FEMINIST, the largest social-first nonprofit media company that is working to build a more inclusive feminist future, had the great idea of being photographed in front of the platform at the center of the room holding the green handkerchief we each received that read, “Nem Presa Nem Morta” (Neither Jailed Nor Dead) from the organization of the same name. (The color symbolizes Latin America’s Green Wave movement, which is shifting the tide on abortion rights and access across the region, most recently in Chile.) A number of us quickly followed Polanco’s lead, wanting our own memento of the experience, as security officers glared; our time was up.

After hearing from legislators, advocates, and organizers in Brazil, it became clear that our communities across the globe already have the tools to ensure that loved ones and neighbors are informed about their options and can stay safe in accessing the services and resources that they need. The threats of criminalization are real and are more severe for people of color. But it was striking to be in Brazil—where people of color in favelas who were unable to afford care in private clinics figured out with pharmacists another use for misoprostol. People are resourceful and will find ways to continue having abortions, no matter who is in office or how the laws change. This is the history of abortion around the world. And today we have ways of documenting and sharing information that were not as available decades ago, let alone hundreds of years ago. Therefore, we have a duty—in whatever role we play—to share the best information about how to seek care safely. The risks are too enormous not to.

Take a stand against Trump and support The Nation!

In this moment of crisis, we need a unified, progressive opposition to Donald Trump.

We’re starting to see one take shape in the streets and at ballot boxes across the country: from New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani’s campaign focused on affordability, to communities protecting their neighbors from ICE, to the senators opposing arms shipments to Israel.

The Democratic Party has an urgent choice to make: Will it embrace a politics that is principled and popular, or will it continue to insist on losing elections with the out-of-touch elites and consultants that got us here?

At The Nation, we know which side we’re on. Every day, we make the case for a more democratic and equal world by championing progressive leaders, lifting up movements fighting for justice, and exposing the oligarchs and corporations profiting at the expense of us all. Our independent journalism informs and empowers progressives across the country and helps bring this politics to new readers ready to join the fight.

We need your help to continue this work. Will you donate to support The Nation’s independent journalism? Every contribution goes to our award-winning reporting, analysis, and commentary.

Thank you for helping us take on Trump and build the just society we know is possible.

Sincerely,

Bhaskar Sunkara

President, The Nation

More from The Nation

Israeli Soldiers Abused Me Before. I’m Terrified That They’ll Do It Again. Israeli Soldiers Abused Me Before. I’m Terrified That They’ll Do It Again.

Israel is invading Gaza City again. The trauma of what they did to me and my family during their last invasion haunts me every single day.

The Ukraine Peace Process Is Moving Quite Fast The Ukraine Peace Process Is Moving Quite Fast

Here are the openings—and obstacles.

Dismantling USAID Wasn’t Just Cruel—It Was Stupid Dismantling USAID Wasn’t Just Cruel—It Was Stupid

In an interconnected world, those who are alone, to use a favorite word of the president’s, are losers.

Trump Won’t Deliver Peace to Ukraine—or Anywhere Else Trump Won’t Deliver Peace to Ukraine—or Anywhere Else

No one can trust the United States when a fickle man-child controls its foreign policy.

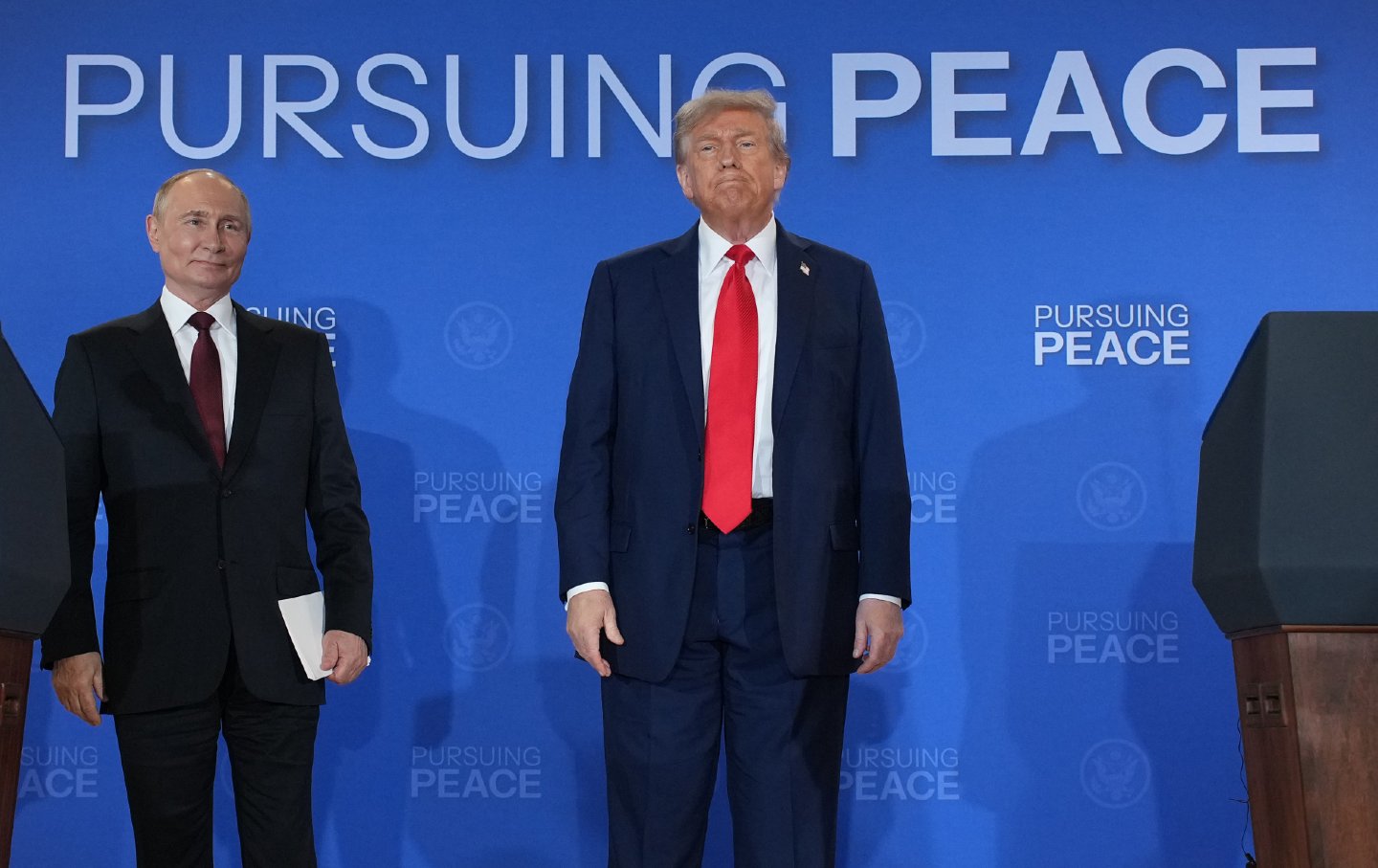

Presidents Trump and Putin Must Seize the Moment in Alaska Presidents Trump and Putin Must Seize the Moment in Alaska

The war in Ukraine is a regional security and humanitarian tragedy, but regarding nuclear weapons, Washington and Moscow stand to benefit from working together.

The Bookstores Bridging Divides in Israel The Bookstores Bridging Divides in Israel

People of goodwill on either side of the horror find unity in the search for a good read.