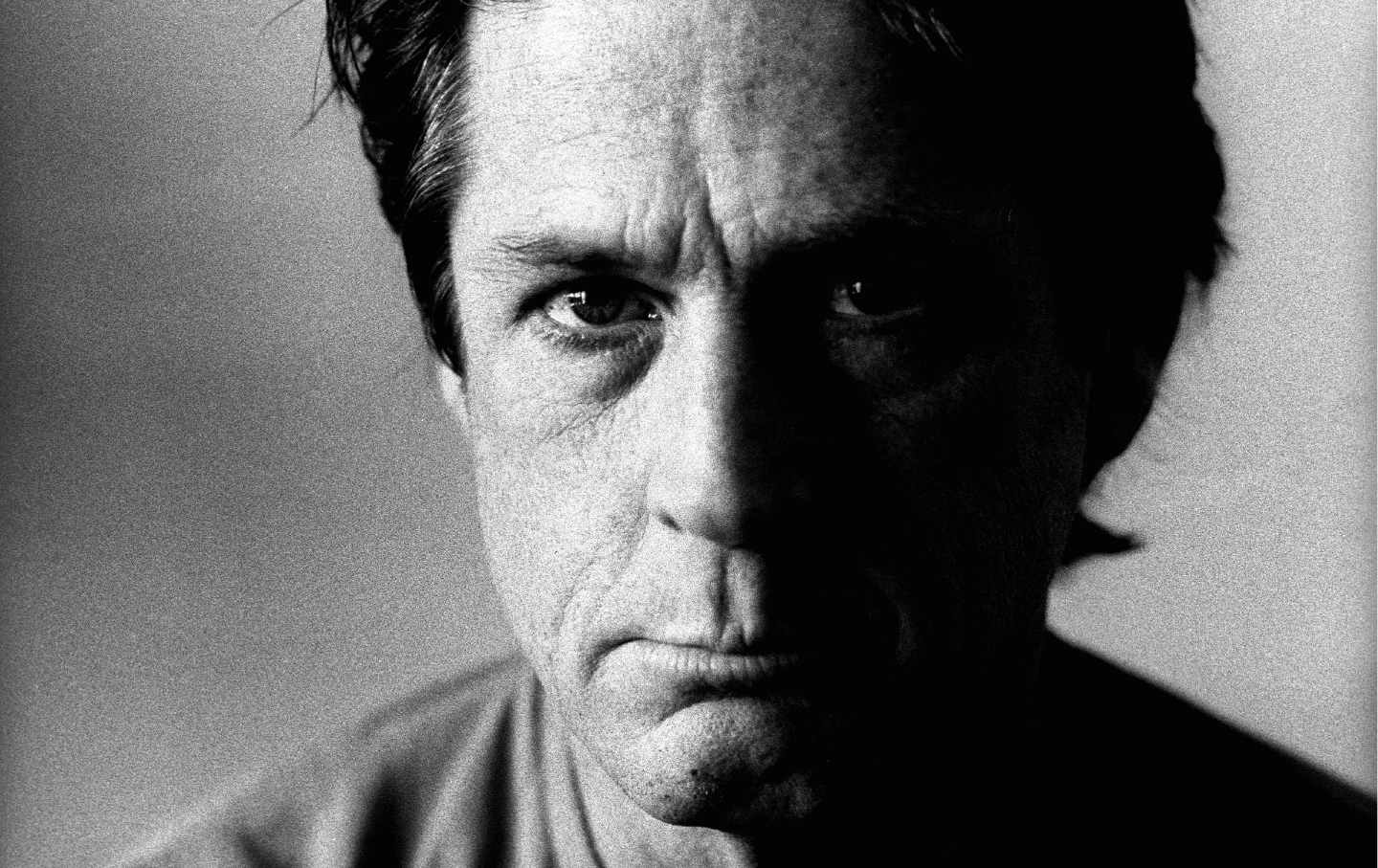

Brian Wilson (1942–2025) Outlived the Times He Helped Define

When the Beach Boys front man died, the obituaries described him as a genius. Which means what, exactly?

Anyone who grew up the 1960s grew up with the Beach Boys. The first time I heard them was on a transistor radio owned by one of the seventh-grade girls who lived in the farm town (pop. 72) where I was then marooned. I was in the second grade, and the song was “Surfin’ U.S.A.,” a rewrite of Chuck Berry’s “Sweet Little Sixteen.” (Berry is said to have first heard the single while he was in prison, serving a two-year sentence for violating the Mann Act.)

The Beach Boys were led by Brian Wilson. Indeed, Brian Wilson was the Beach Boys. He largely wrote, performed, and produced the recordings they made in the 1960s, from “Surfin’” in 1961 to “Do It Again” in 1968—the latter filled with nostalgia for a time in their lives that was then no more than five years in the past (a foretaste of their later career as purveyors of harmless memories)—and his voice, especially his falsetto, was a distinctive part of their sound.

Remembering Brian Wilson

But those facts—his melodies, his work in the studio (when rock gods die, their photographs usually portray them on stage; Wilson was shown at a sound board), even his vision of a distinctively American way of being as exemplified in the guileless lyrics and keening guitars of “I Get Around,” “Fun Fun Fun,” and “Be True to Your School” (my late father’s favorite; he was only seven years older than Wilson)—hardly explain Wilson’s legacy. When Wilson died recently, at the age of 82—when or where is still unclear—obituary writers leaped to describe him as “a genius.”

Which means what exactly?

For Wilson, it meant at least in part that he transcended understanding. In some ways, the music he made was puerile—the lyrics were often contemptible, the instrumental backing either undercooked or overwrought. Even masterpieces like “California Girls” and “Good Vibrations” are faintly ridiculous, more aspiration than achievement. Yet who can listen to “Caroline, No,” the concluding track—leaving aside the sounds of dogs barking and trains whistling—on the Beach Boys’ finest long-player, Pet Sounds, without being deeply moved?

Wilson was strange—probably mad—and it was his strangeness that contributed as much as his music to his reputation as a genius. Even in videos of the Beach Boys performing in the early 1960s, he appears to be searching for an exit. The breakdown that led to his forsaking live performance; the piano in the living-room sandbox; his panicked abandonment of Smile (the intended, and soaringly ambitious, follow-up to Pet Sounds); his wandering the aisles of his very own health-food store, the Radiant Radish, in a bathrobe—all became part of his legend.

And now Brian is dead, far outliving his brothers—the 39-year-old Dennis, who drowned in 1983 after a day of drinking, and the dutiful Carl, who died of cancer, then 51, in 1998—and most of his bandmates. (Of the Beach Boys most will remember, only his cousin Mike Love and his high school friend Al Jardine, survive.) More to the point, he had outlived the times he helped define. Yet the 45s and the best of the LPs—The Beach Boys Today!, Summer Days (and Summer Nights!!), Pet Sounds, even Smiley Smile, which was definitely not Smile—endure. Come summer, the title of one of the Beach Boys’ greatest-hits albums, Spirit of America, never seems truer. It is the music my Gen X wife and millennial daughters (and as one day, I am sure, my Gen Beta grandson will) all demand with their hot dogs and Cokes.

Of course, there was another America even then—as the recent death of another visionary, Sly Stone, serves to remind us. (Stone was also 82, make of that what you will.) Like Wilson’s Beach Boys, Sly and the Family Stone made music in the ’60s—“Dance to the Music,” “Everyday People” and “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)”—that was both joyful and, so baby boomers like me imagined at the time, inclusive. And yet, also like Wilson, there was a strangeness to Sly Stone as old as “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” The evidence was in the grooves of his early-’70s album There’s a Riot Goin’ On—along with Wilson’s “Surf’s Up” (a remnant of Smile released in 1971), a troubled foreshadowing of the failing dream we now all share.

Take a stand against Trump and support The Nation!

In this moment of crisis, we need a unified, progressive opposition to Donald Trump.

We’re starting to see one take shape in the streets and at ballot boxes across the country: from New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani’s campaign focused on affordability, to communities protecting their neighbors from ICE, to the senators opposing arms shipments to Israel.

The Democratic Party has an urgent choice to make: Will it embrace a politics that is principled and popular, or will it continue to insist on losing elections with the out-of-touch elites and consultants that got us here?

At The Nation, we know which side we’re on. Every day, we make the case for a more democratic and equal world by championing progressive leaders, lifting up movements fighting for justice, and exposing the oligarchs and corporations profiting at the expense of us all. Our independent journalism informs and empowers progressives across the country and helps bring this politics to new readers ready to join the fight.

We need your help to continue this work. Will you donate to support The Nation’s independent journalism? Every contribution goes to our award-winning reporting, analysis, and commentary.

Thank you for helping us take on Trump and build the just society we know is possible.

Sincerely,

Bhaskar Sunkara

President, The Nation