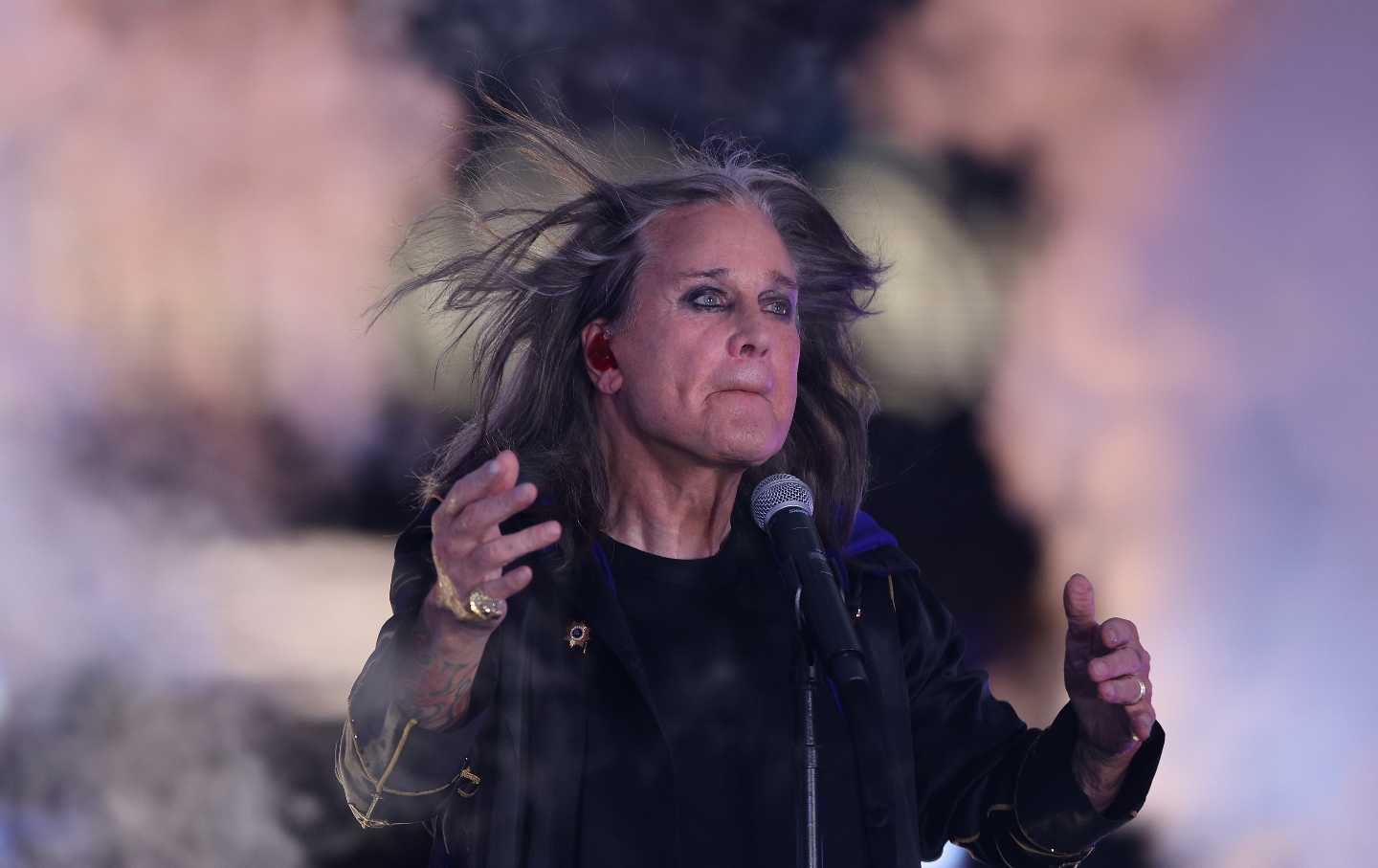

Ozzy Osbourne, Rock God Despite Himself (1948–2025)

The Prince of Darkness, who gave us heavy metal as we know it, has been laid to rest.

Rocking right up until the end.

(Harry How / Getty)

“Iwas the kind of kid who always wanted to have fun, and there wasn’t much of that to be had in Aston. There were just grey skies and corner pubs and sickly looking people who worked like animals on assembly lines,” John Osbourne once wrote. By the time he was born, in 1948, his aforementioned hometown, Aston, was a struggling working-class suburb of Birmingham, England, that still bore the scars of World War II bombings. It offered few opportunities for young men like him, the sensitive son of a toolmaker and a factory worker. After a brief and rather insalubrious career of petty crime landed him in jail at the age of 17, Osbourne decided to get his first proper job—as a “puke remover” in a slaughterhouse, cleaning out sheeps’ stomachs. By then, he’d already fallen in love with the Beatles, and dreamed idly of following them—another bunch of rough, working-class lads, just like him—into the music world. “Never in a million years did I think I’d end up making a career out of singing,” he later reflected. “As far as I knew, the only way I could make any dough was to go and work in a factory like everyone else in Aston. Or rob a fucking bank.”

Osbourne soon graduated to “cow killer,” and might have spent the rest of his career working his way through the killing floor were it not for an ad he taped to a local music shop’s window in 1968. The most significant of the responses he got to his “Ozzy Zig Needs Gig—has own PA” ad came from three local lads named Bill Ward, Terry Butler, and Tony Iommi, who wanted to form a band. The rest, as they say, is heavy metal history. The quartet’s first collective musical attempt, the Pulka Tulk Blues Band, gave way to the off-kilter, blues-heavy Earth, which by 1969 had morphed into a little band called Black Sabbath that was as inspired by horror movies as by the band members’ own grim existence. Thanks to guitarist Iommi’s own factory experience, during which a gruesome accident cost him the tips of two of his fingers, he was forced to tune his guitars down low and use heavier strings, which resulted in a menacingly heavy, saturnine sound that immediately stood out in the Flower Power ’60s. There had been other heavy rock bands before them, like Deep Purple, Iron Butterfly, Arthur Brown, and especially Coven, but nobody sounded like Sabbath—and nobody, but nobody, sounded like their inimitable singer, John “Ozzy” Osbourne, who would forever be better known by the nickname he’d tattooed on his knuckles with India ink at age 17.

By the late ’60s/early ’70s, when heavy metal emerged, heroic vocals were already an established feature, from the operatic howl of Judas Priest’s Rob Halford to the gruff snarl of Motörhead’s mononymous Lemmy to the ensorcelling croon of Coven’s Jinx Dawson, but Ozzy was one of a kind. He wailed, he warbled, he howled, he ranted, that nasal tenor weaving spells in smoke as he stretched his haunted vocal chords to their absolute limits. Later, he barked at the moon, laughing maniacally, his Brummie burr–obscured and untrammeled theatricality on full display. After Black Sabbath’s self-titled debut album dropped in 1970, it took off like a shot, rocketing to number eight on the UK charts despite negative press attention. A string of stone-cold classics followed—1971’s Paranoid and Master of Reality, 1972’s Vol. 4, 1973’s Sabbath Blood Sabbath, and 1975’s Sabotage. By then, Osbourne’s own demons had begun catching up with him; the whole band partied plenty hard, but he took it to a level that worried his friends and alienated his bandmates. In 1977, Ozzy Osbourne left Black Sabbath. A year later, he went back, only to be fired by the band in 1979. It would be nearly 20 years before the original Sab Four would assemble again, and the 1997 reunion wouldn’t be the last time Osbourne would dip in and out of the fold, either.

By then, Sabbath’s erstwhile singer had carved out a successful solo career, putting his pipes to good use and recording chart-topping albums even as his own health seesawed and legal battles with his on-again, off-again, on-again bandmates muddied the heavy metal waters. By launching Ozzfest in 1996, he paid his own luck forward by creating a space for the next generation of young metal bands to benefit from playing for the massive audiences the Ozzy name still drew. The festival injected vital new blood into the growing and diversifying metal community that he and the Aston lads had helped forge decades before, and provided a crucial early platform for many of metal’s now-mainstream stars (though 2010’s one-off Ozzfest Israel was disappointing on multiple levels).

After selling millions upon millions of albums with Black Sabbath and his solo projects as well as benefiting from Ozzfest proceeds, Osbourne was in a better place financially than he could have ever imagined back in his cow-killer days, but life remained a challenge. Instead of postindustrial decay holding him back, this time it was all him.

He became a rock god almost in spite of himself. During the 1980s, the singer’s addiction to drugs and alcohol fueled the kind of erratic, self-destructive behavior that casual fans and onlookers still bring up whenever his name is mentioned—pissing on the Alamo, terrorizing music industry executives, the infamous bat incident, et al. More seriously, Osbourne was also accused of physically assaulting his then-bandmates Randy Rhodes and Rudy Sarzo, and strangling his manager turned wife, Sharon Osbourne (née Arden), during blackout periods. He was booked for attempted murder, but Mrs. Osbourne declined to press charges, stating that “the person who all but choked me to death was so far gone on drink and drugs that it wasn’t him.”

Osbourne decided to get sober for the sake of their growing family, which he had admittedly neglected during his wilder years. On March 5, 2002, the rest of the world got to meet them when The Osbournes premiered on MTV and turned Ozzy, Sharon, and two of their teenage children, Kelly and Jack, into America’s first reality-TV celebrities overnight. The show, which was inspired by a 1997 BBC documentary and followed the various Osbournes around their luxurious Beverly Hills mansion, introduced the viewing public to a version of Ozzy that must have seemed utterly alien to anyone who knew him growing up, or even at the height of his heavy-metal hedonist days. The family was conspicuously, ridiculously wealthy, and acted like it. We watched the former slaughterhouse worker from a hardscrabble background shuffling around his palatial home like a confused granddad, mugging for the cameras and hollering plaintively for his wife to solve any and every momentary problem. It was a gothic pastiche of a country gentleman gone to seed, and not at all rock ’n’ roll.

To be fair, the man was in his mid-50s and had already survived decades of drug abuse and a physically demanding schedule (being a rock god does take work, even if it’s not exactly clocking in at the sheet metal factory). He’d let slip that he was mortal, and his health issues were already advancing; in 2003, the year after the show’s debut, he would be diagnosed with a form of Parkinson’s, which would contribute to his eventual demise in 2025. But it was still jarring to those in the heavy metal world to see one of their longtime heroes portrayed as such a fabulously rich, out-of-touch cartoon. Those who cared less (or not at all) about his musical accomplishments took the opportunity to point and laugh, to regard him as a clown, to shrink his legacy down to “weird old guy on TV who eats bats or something.”

The show gave his career a needed boost and turned him and his family into bona fide celebrities, but one wonders whether it was worth it. Other metal legends of his caliber like Rob Halford and Bruce Dickinson from Iron Maiden certainly enjoy the fruits of their labors (and Dickinson in particular loves a headline) but have managed to retain their gravitas; even Osbourne’s own bandmates have mostly preferred to avoid the spotlight unless promoting various new projects, and their reputations as metal statesmen remain intact. In contrast, Ozzy chose to give more of himself, to let the world peek into the Prince of Darkness’s cupboards and rummage around. What we found wasn’t always pretty, and made some wonder if he’d forgotten where he’d come from. Instead of raging against the capitalist machine that had once offered him and his friends nothing but hopelessly dead-end jobs, he’d joined the elite. In his later years, he could be found clashing with unions and aligning himself with the kind of conservative forces he’d long disparaged (that’s without even getting into his wife’s fervent Zionism and his own decision to play Israel twice—so much for shouting down war pigs). What would John Osbourne from Aston think?

One imagines he’d argue that he’d done pretty well, considering. Going from a gig shoveling pig guts to being one of the most well-known and internationally beloved music icons of all time is a pretty decent step up for a kid who later swore that his highest aspiration had been to be a plumber. That’s the part of the story that generations of aspiring musicians have latched onto, even if they had to work harder to make up for whatever social or cultural or economic shortcomings they may have had looming over them like the dark Satanic mills of old.

Sabbath’s success and Ozzy’s own career in particular showed the world that you don’t have to be polished or glamorous or come from money to make rock ’n’ roll that mattered; you could be depressed and strange and come from a place nobody cared about, and make it just the same. That’s the part of Osbourne’s colorful life that most of us can actually relate to, and that still shines even now that the majestic old showman has finally exited stage left for the final time at the ripe old age of 76—less than a month after staging a massive farewell concert in Birmingham with all his friends and musical progeny.

Black Sabbath and the genre they spawned have always been working-class music made by working-class people for other working-class people. There’s a reason heavy metal was born in the Midlands and glam rock started in London—you need that grit, that sense of being an outcast, that blood and sweat on the line to truly tune down low and meet the Devil. With Ozzy gone, the genre has lost one of its brightest stars, a true original and a messy, complicated man with a lifetime of wrestling demons etched into his tattooed flesh. We’ll survive without him, but it’ll hurt. It’s harder than ever for young heavy metal bands to make it out there, but at least they know it’s possible. As his lifelong friend Terry “Geezer” Butler wrote the day the news broke, “4 kids from Aston—who’d have thought, eh?”

Take a stand against Trump and support The Nation!

In this moment of crisis, we need a unified, progressive opposition to Donald Trump.

We’re starting to see one take shape in the streets and at ballot boxes across the country: from New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani’s campaign focused on affordability, to communities protecting their neighbors from ICE, to the senators opposing arms shipments to Israel.

The Democratic Party has an urgent choice to make: Will it embrace a politics that is principled and popular, or will it continue to insist on losing elections with the out-of-touch elites and consultants that got us here?

At The Nation, we know which side we’re on. Every day, we make the case for a more democratic and equal world by championing progressive leaders, lifting up movements fighting for justice, and exposing the oligarchs and corporations profiting at the expense of us all. Our independent journalism informs and empowers progressives across the country and helps bring this politics to new readers ready to join the fight.

We need your help to continue this work. Will you donate to support The Nation’s independent journalism? Every contribution goes to our award-winning reporting, analysis, and commentary.

Thank you for helping us take on Trump and build the just society we know is possible.

Sincerely,

Bhaskar Sunkara

President, The Nation

More from The Nation

The Empty Provocations of “Eddington” The Empty Provocations of “Eddington”

Ari Aster’s farcical western is billed as a send-up of the puerile politics of the Covid years. In reality, it’s a film that seems to have no politics at all.

The Rot at Fort Bragg The Rot at Fort Bragg

Seth Harp exposes how all the death and crime surrounding one military base is not an aberration but representative of the fratricidal impulse of the armed forces at large.

The Revolutionary Politics of “Andor” The Revolutionary Politics of “Andor”

The latest addition to the "Star Wars "series offers an intricate tale of radicalization and its costs.

Billy Wilder’s Battle With the Past Billy Wilder’s Battle With the Past

How the fabled Hollywood director confronted survivor’s guilt, the legacies of the Holocaust, and the paradoxes of Zionism.

The Art and Genius of Lorna Simpson The Art and Genius of Lorna Simpson

A new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art tracks what has changed and what has remained the same in the artist’s work.

Catherine Lacey’s Missed Connections Catherine Lacey’s Missed Connections

In her most personal work, "The Möbius Book", Lacey uses a devastating moment of heartbreak to ruminate on the messy intersections between life and writing.