To Make Democracy Work, Give More of It to Workers

The fight to reclaim American democracy has to begin with our oligarchic political economy.

An Amazon worker affiliated with the Teamsters on strike at a company delivery hub in Maspeth, Queens, last year.

(Selcuk Acar / Anadolu via Getty Images)The 2024 election was a referendum on democracy—one that democracy lost fair and square. As loudly and as forcefully as Joe Biden, Kamala Harris, and the Democratic Party as a whole argued that Donald Trump posed a threat to America’s democratic institutions, he was reelected with both an Electoral College majority and the Republican Party’s first popular vote plurality in 20 years. The polls suggest many wound up backing Trump for economic reasons—as troubled as they might have been by his antidemocratic rhetoric and effort to overturn the 2020 presidential election, the hope that Trump could ease the cost of living won out over the warnings about his authoritarianism and the democratic abstractions that became central to the Harris campaign’s closing message.

That was only partially the Harris campaign’s fault—by habit, we tend to fret about the state of our political institutions and the state of our economy separately. But our understanding of democracy, and our defenses of it, should be shaped by materialism—an understanding that economic conditions and alignments of economic power determine the extent to which the governed can govern. Our Constitution, for instance, was profoundly shaped by economic conditions at the time it was written. Troubled by the demands struggling Americans were making of government after the American Revolution, our founders designed a federal system that frustrates our ability to democratically address our economic concerns and other matters to this day. And money in politics today has made matters worse—on top of the Constitution’s antidemocratic design, corporations and the wealthy shape policy in ways visible and invisible to ordinary Americans on the outside looking in.

Fixing the latter problem would take more than imposing new limits on how the economic elite can directly engage in politics, as important as that goal remains. Corporations and the wealthy exert their political influence through a variety of indirect channels, from the media to their social circles. This means that an ordinary American would still wield far less political power—and be far more subject to political domination—than a millionaire or billionaire even with major campaign finance and lobbying reforms.

But another way to counter the domination of the wealthy in our politics would be to democratically restructure the economy—granting the American worker more agency and ensuring that economic power and resources accrue to more than a wealthy few in the first place. In doing so, we’d not only reduce inequality to the benefit of our political institutions, but also, of course, to the material benefit of everyday Americans—demonstrating that democracy is worth fighting for not just as a political abstraction but a means of improving our working lives.

In the 1980s, the democratic theorist Robert Dahl posed a key question often overlooked in both our political reform and economic policy debates: “What about the ownership and control of economic enterprises as a source of political inequality?”

Ownership and control contribute to the creation of great differences among citizens in wealth, income, status, skills, information, control over information and propaganda, access to political leaders and, on the average, predictable life chances, not only for mature adults but also for the unborn, infants, and children. After all due qualifications have been made, differences like these help in turn to generate significant inequalities among citizens in their capacities and opportunities for participating as political equals in governing the state.

As Dahl observed, the design of our basic economic institutions—including the structure and ownership of companies—clearly matters. It’s plain that our efforts to tackle inequality will be incomplete unless we’re willing to address how they produce inequality to begin with. And beyond the fact that the wealth and economic power that accrues to investors and those at the top of firms is leveraged for influence within our political institutions, the subordination of workers is also democratically troubling in itself.

We spend roughly a third of our lives at work and earn our livelihoods there. The decisions made in corporate boardrooms and on Wall Street often affect us more directly, immediately, and intimately than decisions that are made in Washington or in our state capitols and city halls. Yet most Americans take it entirely for granted that we’re not entitled to a say in how the companies we work for function. This should change. If democracy is desirable because it gives us a measure of agency over the conditions that shape our lives—helping us master our own fates rather than living as the mere subjects of the powerful or the victims of circumstance—we should work to bring democratic values into the economy.

Though we’ve long forgotten it, the coming of “economic democracy”—and, specifically, democracy within firms—was once seen as an inevitable development by many thinkers and political figures, particularly in the first half of the last century. In the aftermath of World War II, for instance, the philosopher John Dewey predicted that the conflict would lead to a democratic revolution in industrial organization. “It is so common to point out the absurdity of conducting a war for political democracy which leaves industrial and economic autocracy practically untouched,” he wrote, “that I think we are absolutely bound to see, after the war, either a period of very great unrest…or a movement to install the principle of self-government within industries.” That didn’t happen. But for a time, the postwar economy did deliver Americans a measure of economic democracy—thanks to the growth of the American labor movement.

While much of the economic growth and prosperity America experienced in the decades immediately following the war was spurred by the social and economic investments of a federal government much bigger and bolder than ours is today, economies are built upon the backs of workers. The drivers and the miners, the clerks and the cooks, those who build and fix and clean and carry, those who staff the factories and the shops—whatever politicians and their donors say about the wealthy “job creators” at the top of companies, it’s the job doers to whom we owe everything. And for generations, job doers seeking a greater share of the prosperity they produce have turned to labor unions. In 1935, the National Labor Relations Act, better known as the Wagner Act, guaranteed most private-sector workers the right to organize and to bargain for better pay and working conditions. As a result, union membership spiked—in the 12 years after its enactment, nearly 11 million Americans joined up.

In 1935, about 13 percent of the country’s workforce had been unionized. By 1955, that proportion jumped to roughly one-third of American workers. Beyond getting the American people a better deal at work, unions used that newfound strength to push the New Deal and Great Society agendas forward—by politically organizing and mobilizing their workers, unions helped win the fights for Medicare and other major programs. Both in the workplace and at the ballot box, unions played a significant role in ensuring that the gains from our economic growth flowed to workers and not just the already wealthy. According to one 2021 paper, increasing union membership alone likely explains nearly a quarter of the decline in American inequality from 1936 to 1968. And while union families earned 10 to 20 percent more in income than nonunion families between the 1940s and the 2010s, unions also made nonunion workers better off than they otherwise would have been—to compete with union workplaces for new hires and to keep their employees content, even nonunion workplaces wound up offering better pay and working conditions.

The gains unions delivered for American workers should be understood as the products of economic democracy. After all, workers form unions by majority rule — either in elections administered by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) or by an employer’s voluntary recognition that a majority of its workers in a given unit have signed cards to form a union. Once unionized, workers are able to exercise real agency through bargaining and to voice their ideas and concerns about work in ways that are protected by law.

Naturally, the wealthy and their backers in Washington fought back against the growth of unions as quickly and as doggedly as they could. In 1947, over a veto by President Truman, Congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act, which imposed a laundry list of restrictions on union activity and included other measures to limit their growth. Among the most significant of them was granting states the ability to pass “right to work” laws, which are often framed as granting workers the right not to join a union. But American workers never have to join unions if they don’t want to—workers who don’t want to be members of a union at their workplaces can instead pay fees that cover the costs of the union’s bargaining activity on their behalf rather than actual union dues. What “right to work” laws actually do is starve unions of resources by ensuring workers in unionized workplaces don’t have to pay unions anything at all.

The proliferation of those laws and the other limitations on labor organizing imposed by the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act put the brakes on the growth of the labor movement. And further disempowering it became one of the cornerstones of the economic agenda that formed in the wake of an economic downturn in the early 1970s—an all-out assault on the policies of the New Deal and the Great Society. Unions were tamed, taxes were slashed, government programs were gutted, government functions were privatized, industries were deregulated, jobs were enthusiastically sent overseas, and finance took up a greater share of our economic activity.

Policymakers assured voters that these changes would eventually deliver economic freedom and prosperity to all Americans. But on the whole, this agenda made the wealthy wealthier and more powerful while ordinary working Americans struggled to adjust. The result has been steadily deepening inequality. And few changes were as dramatic or consequential as the fall of the labor movement. From its peak at roughly one-third of the American workforce in the 1940s and 1950s, union membership has declined to about 10 percent of the workforce today, including just 6 percent of the private-sector workforce. According to one estimate, the decline in union membership since 1968 accounts for about 10 percent of the increase in income inequality America has seen since then. According to another, when the impact on the hourly wages of nonunion members is factored in, the decline of unions likely explains as much as one-fifth of the rise in wage inequality among American women and one-third of the rise among American men working in the private sector from 1973 to 2007.

Companies are working hard to cripple unions even further. Although the Wagner Act prohibits them from explicitly firing or punishing workers for trying to unionize, U.S. employers spend more than $400 million a year on consultants who specialize in discouraging or thwarting unionization efforts with a variety of tactics that skirt the edges of legality. And even when companies engage in flagrantly illegal activity—firing unionizing workers, say, or spying on employees who are organizing—the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) cannot directly impose monetary penalties on them for breaking the law.

That weakness has made employers brazen. In recent years, major firms such as Starbucks, Chipotle, Walmart, and Trader Joe’s have not just fired workers trying to organize but have also shut down entire stores with ongoing union activity, supposedly for unrelated reasons. And as union organizers know well, even when a union is formed, negotiating a labor contract can be a long, drawn-out process, thanks in substantial part to the company’s stalling tactics.

This landscape, combined with the growing difficulty of organizing, has taken power away from workers and given an increasing share of it to executives and wealthy investors on Wall Street.

In recent years, unions and advocates hoping to wrest that power back have united in support of the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act—the most significant piece of proposed legislation for organized labor since the Wagner Act. An override of state right-to-work laws; a ban on forced anti-union meetings at work; a ban on permanently replacing striking workers; a ban on forcing employees to waive their right to class-action lawsuits; civil penalties for violations of the Wagner Act; and a presumption in law that workers are employees rather than independent contractors unless employers can prove otherwise—these and the PRO Act’s other provisions would be utterly transformative, making it easier to organize unions, bolstering their power, and extending new protections to all workers, both union and nonunion.

Still, more could be done. Federal labor law could be changed so that a union is automatically formed and recognized by the NLRB once a majority of employees in a given unit sign cards authorizing one—without the need for a separate election. And workers should have the right to bargain over more in union contracts than “wages, hours and other terms and conditions of employment,” as the Wagner Act currently allows. Harvard Law’s Sharon Block and Benjamin Sachs have noted that workers have mounted internal protests at a variety of firms recently over issues like climate change and the injustice of Donald Trump’s immigration policies. As they argue, “the democratic principles that give workers a claim to voice over wages and hours similarly demand workers have voice in these other decisions that their firms make and that have profound impacts on the workers and their communities.”

What’s more, the Wagner Act has never covered public employees or agricultural and domestic workers. Federal law should grant them the same labor rights as all other workers. It should also end at-will employment by establishing that workers can be fired only for just cause—a reform that would not only grant American workers a basic protection afforded to nearly all other workers in the world, but also facilitate the formation of unions by making it more difficult for employers to invent reasons for firing union organizers and pro-union employees. It should also be established that federal labor law, once reworked, should be the floor for labor protections in this country rather than the ceiling. States and localities should be allowed to pass labor laws of their own, provided they are at least as protective of unions and workers as federal legislation is.

While these policies would surely rejuvenate and expand unions, it must be remembered that even at peak membership, the vast majority of American workers have never been represented by a union—thanks, in part, to a system that forces workers to organize themselves piecemeal, individual workplace by individual workplace. To broadly unionize retail workers as a whole, for instance, would require unionizing countless individual workplaces at a multitude of companies across the retail sector—an extraordinarily daunting task. Expanding the reach of union contracts could help here. Unions have at times been able to negotiate master contracts that cover workers at multiple companies. Labor law could be changed to help make those agreements more common—once workers at a few workplaces reach similar contracts, for instance, the law could have those contracts automatically cover other newly organized workers in the same region and sector, without each workplace having to negotiate separate agreements.

Policymakers could also more fundamentally transform labor law by instituting sectoral bargaining—a system in which representatives of employers and unions come together to negotiate over and set basic pay and conditions for workers across entire sectors of the economy all at once. On bargaining panels, those representatives might craft and vote on agreements that (for example) set a minimum wage-and-benefits package for all retail workers in a given state or region, rather than waiting for workers to organize unions and negotiate contracts store by store. New union chapters could then focus on negotiating issues specific to each workplace, or try to push for even better pay and conditions than the minimums established by the bargaining panels.

Sectoral bargaining has a number of advantages beyond being a quicker and easier way to improve things for workers than depending solely on traditional union organizing. For one thing, companies might be less resistant to improving pay and conditions for workers if all their competitors were made to do the same in a sectoral agreement. (As matters stand now, one reason companies fight hard against unions is that they fear spending more on their workers will put them at a competitive disadvantage against their rivals.) For another thing, sectoral agreements could address the now-common management strategy of “fissuring” workers in contracting arrangements and gig-economy employment by protecting all workers doing the same kind of work. “It matters not whether someone is employed directly, is employed by a subcontractor or by a franchisee, or is an independent contractor,” Block and Sachs explain. “If they work in the sector, they are covered by the sectoral collective bargaining agreement.”

But perhaps most important of all, sectoral bargaining panels—each a kind of legislature governing work in a particular sector—would be a remarkable instantiation and expansion of economic democracy. And that would be especially so if all the workers in a sector could elect the union members who represent them on each panel. As dramatically different as sectoral bargaining would be from the status quo, the seeds for it have already been sown. At various points over the last century, the federal government established boards and committees with business and labor representatives to set or advise on wage standards. And in recent years, policymakers in states and cities across the country have established similar “wage” and “workers’ boards” to set or advise on wages and working conditions—such as California’s Fast Food Council or Colorado’s board for direct care workers. Efforts like these should be expanded and made more fully democratic—allowing for the election of worker representatives by workers themselves—on the way to true sectoral bargaining in America.

Unions and bargaining are far from the only ways that we might build democratic agency for workers. Here, US policymakers should take a page from Europe—with reforms that would give workers a direct say in business decisions. One such reform would be to have businesses institute work councils—bodies of representatives, elected by workers, that are consulted on working conditions, firings and layoffs, and other matters directly affecting employees’ lives at work. While councils in most countries are merely informed of certain impending decisions, a few countries like Sweden and Germany have given their councils a degree of real authority over working conditions. Contrary to what skeptics might assume about the business sense of granting worker representatives that much power, research has shown that work councils have no impact on a firm’s profitability. If anything, they may increase productivity—perhaps by offering workers forums in which they can discuss and solve problems. That makes work councils a good supplement for traditional unions: They can address new or specific issues in the workplace atop the contracts that unions have already negotiated. They can offer workers a voice in workplaces where a union has yet to be organized. The fear that work councils could be used to manipulate workers—through representatives undermined, selected, or controlled by managers—led to the adoption of provisions in the Wagner Act that essentially banned them in the United States. But those concerns should be allayed by new laws mandating that companies put councils in place when workers themselves demand them, and protecting such assemblies from the interference of bosses (much like the Wagner Act’s protections for those trying to organize unions).

Workers should also be given democratic power at much higher echelons of corporate governance. In some countries, companies are required, under an arrangement known as codetermination, to reserve for their workers a portion of the seats on their governing boards, ensuring that ordinary employees get at least some say in decisions that might otherwise be left wholly to executives and investors. Germany’s system is perhaps the most well known and widely studied. There, most companies with 500 to 2,000 employees are required to have their workers elect one-third of the supervisory board that chooses and manages the executives running the company. Most companies with at least 2,000 employees are required to have their workers elect one-half of that board. And, as with work councils, research suggests that firms with codetermination are as or more productive than others.

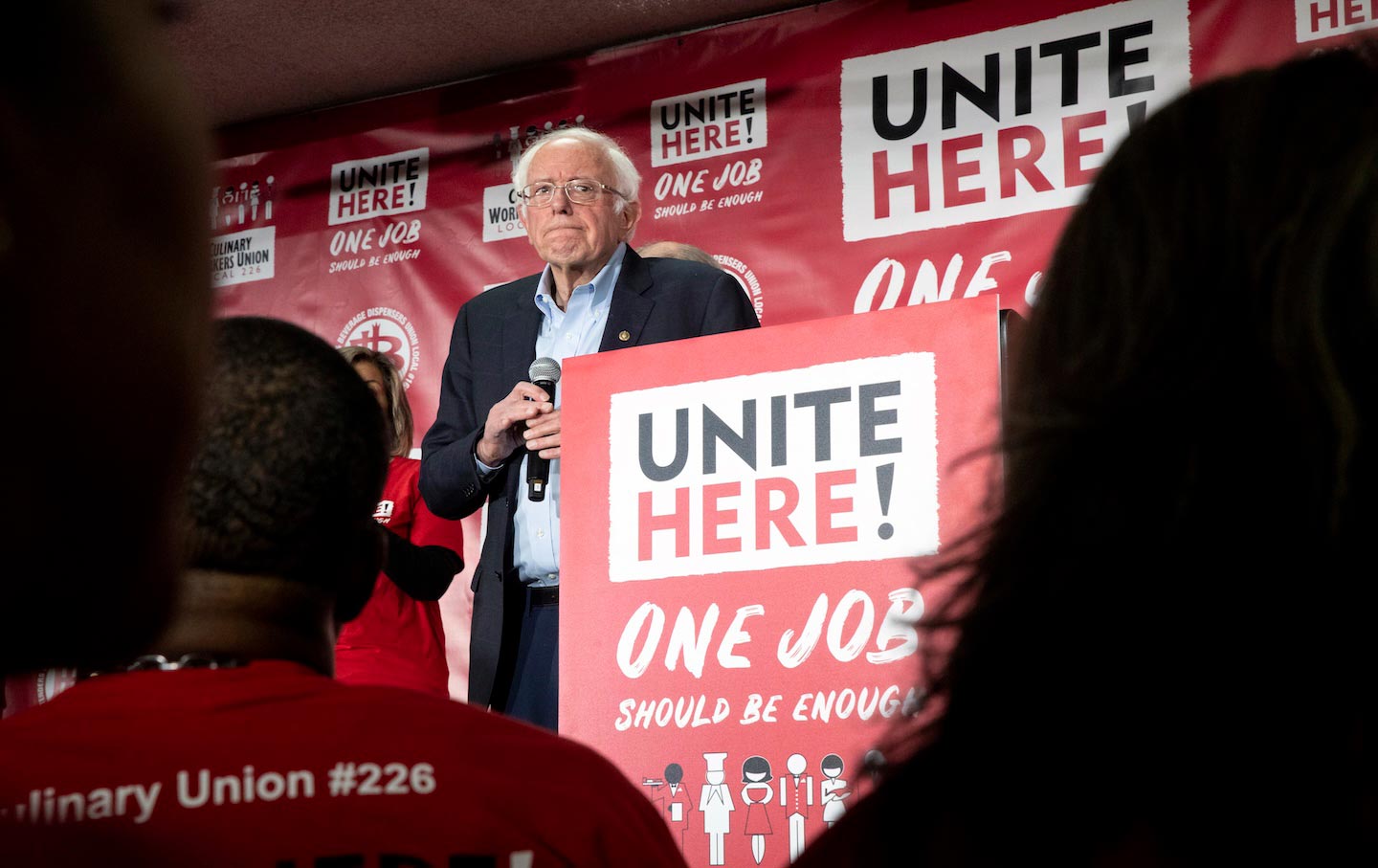

In 2018, Wisconsin Democratic Senator Tammy Baldwin introduced a bill that would have required all corporations on the stock market to let workers elect at least one-third of their board of directors. This was followed by presidential-campaign proposals from Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders. Warren would have required companies collecting at least $1 billion in revenue to let workers elect 40 percent of their boards. Sanders would have had all companies on the stock market, as well as companies with at least $100 million in assets or revenue, let their workers elect 45 percent of their board. Either way, the Warren and Sanders proposals would have applied to companies employing roughly 30 million workers.

Under the Baldwin, Warren, and Sanders plans, employee power would obviously be limited. As is just about universal in all codetermination schemes, worker representatives would have only a minority of seats on each board. Still, granting workers elected seats at the table where corporate decisions are made would significantly empower them. Even with a minority of seats, worker representatives could deeply influence corporate governance by casting key votes on issues where other board members might be split, and ensuring that matters important to workers are raised for discussion. And they could use that influence to help bolster the democratic power of workers elsewhere—by pushing back against company efforts to discourage or frustrate union organizing, for instance, or by trying to rein in political contributions to anti-union candidates and groups.

But even if workers were on their boards, companies would still fundamentally be accountable to those who own them— founders, executives, and anyone else owning company shares. For public companies, that includes Wall Street investors who buy and profit from stock sold in the markets without contributing anything whatsoever to a company’s operations and success. Shareholders can vote on corporate matters— including selecting company board members—and the dividends that boards decide to pay out. A company’s actual employees, on the other hand, are generally entitled to none of this. Unless their employers are generous, they earn nothing more from the wealth their work produces than their pay and benefits—no shares or income as their companies do well, no votes as shareholders. Even with all the reforms explored above, those wealthy or well-placed enough in the company to own stock would still be calling the shots.

Given all that, workers should also be owners, entitled to an ownership stake in the companies they work for. Some already are. According to Rutgers professor Joseph Blasi, about 10 to 20 percent of companies on the New York Stock Exchange and NASDAQ have substantial programs where some stock is either granted to employees or offered to them at a discount. That includes corporations such as Alphabet (Google), Apple, ExxonMobil, Ford, Goldman Sachs, and Microsoft. And at some private companies, employees can come to own a substantial proportion of shares. The supermarket chain Publix, for instance—one of the top 10 largest private US companies—is fully owned by its 250,000 employees and its founder’s family.

For years now, the primary vehicle for achieving worker ownership at that scale in the United States has been the employee stock-ownership plan (ESOP). In an ESOP, a company’s stock is gathered from various sources and placed in a trust for employees, who receive an allocation of shares that the company can buy back from them for cash once they retire. About 6,500 companies employing some 14 million workers—about 10 percent of the private-sector workforce—have ESOPs today. Roughly 2,000 of them are wholly owned by their employees. And research suggests that employee ownership is both good for workers and good for business. Companies with ESOPs tend to grow faster and are more productive after starting such plans than they would have been otherwise. Privately held ESOPs are also less likely to go bankrupt, and ESOP workers are less likely to be laid off. While some might assume that companies with ESOPs would compensate for the stock given to employees by reducing wages, evidence shows that the wages of employees at such firms may, if anything, be higher.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →From a democratic perspective, most ESOPs have one key limitation: Workers usually lack a direct voice in corporate governance as shareholders. Instead, ESOPs are run by trustees, who vote for employees on most matters (except major changes, such as a company’s sale or merger). Yet they can be structured differently. Employees could be allowed to vote directly on more matters, for example, or they could be given the right to control the votes cast by trustees. The tax and other government incentives and supports that flow to ESOPs could be amended specifically to encourage the formation of ESOPs of this kind.

In 2019, Bernie Sanders proposed another democratically promising and ambitious model for worker ownership, inspired by an idea floated by the UK’s Labour Party. Under his plan, the federal government would pass a law requiring all companies on the stock market and all companies with at least $100 million in revenue or on their balance sheets to establish what he called Democratic Employee Ownership Funds (DEOFs), controlled by worker-elected trustees. Each company would then gradually place 20 percent of its stock into its DEOF over 10 years. And workers at each company would have the right to vote through their portions of stock in the fund, just like any other shareholders.

In plainer terms, the Sanders plan would have given workers ownership and control over 20 percent of every major company in the country—every big corporation you’ve heard of and thousands more besides, employing some 56 million Americans. And their ownership stakes would entitle workers to both full voting rights as shareholders and additional income from dividends worth, according to one analysis, an average of at least $2,622 per worker per year at publicly traded companies. As far-reaching and transformative as Sanders’s own proposal is, evidence suggests there may be public support for taking it even further. In 2019, a survey found that a majority of Americans would support companies with more than 250 employees transferring as much as 50 percent of their stock to worker funds, making them halfway worker-owned and worker-controlled.

Beyond ESOPs and the funds envisioned by Sanders, there are fully fledged worker cooperatives—companies directly owned and controlled by their workers. In a cooperative, the divisions between workers and managers are eroded or erased to establish self-government. Collectively, it’s up to the workers in a cooperative to decide what the business should do, and then to do it. The profits, like the employees’ responsibilities, are divvied up among themselves. The worker-cooperative sector in most countries is small. In the United States it is positively tiny—by one estimate, there are perhaps 1,000 such enterprises in America, employing some 10,000 workers. But cooperatives are nonetheless instructive, illustrating how much workers are capable of when left to their own devices—and how well democracy at work can function as a practical matter. Consider Spain’s Mondragon Corporation, perhaps the best-known collection of cooperatives in the world, which employs tens of thousands of workers across some 95 firms in a variety of industries. “The collective enforces five hundred and five types of patents and employs about twenty-four hundred full-time researchers,” New Yorker contributor Nick Romeo wrote in 2022. “The odds are good that key elements of something within a hundred feet of you—an espresso maker, a gas grill, a car—were made at Mondragon.”

In general, cooperatives—as large as Mondragon or much smaller—tend to be about as profitable and grow about as much as traditional companies, while offering their workers more job security. They do come with their own unique challenges— worker congresses, like all congresses, do not always work well, and full participation in cooperative governance can demand a lot from workers. But they’re a viable and democratically empowering business model, and we could do more to foster them. States can pass legislation laying out how cooperatives should be incorporated to help them comply with state laws built around more traditional businesses and secure funding from banks. Tax breaks and loans can be offered to help start cooperatives or convert existing businesses into them. And more worker-ownership centers, like those in Sanders’s Vermont, could be founded with government support to offer them resources and technical assistance.

Pursuing the agenda described here would remake the American economy once again, this time to the benefit of America’s workers—reducing inequality, improving the conditions of their working lives, and dramatically expanding their democratic agency in ways that will pay off not only at work but within our politics. Empowering workers and the unions advocating on their behalf could hamper the anti-worker political activities of their employers. And putting more money in workers’ pockets could facilitate democratic participation—it’s much harder to be an involved and attentive democratic citizen, after all, if you’re not sure how you’re going to pay your bills next month.

But economic democracy would bolster political democracy in another way. Democracy is a vastly complicated thing; like all complicated things, engaging in it well takes practice. Habits and skills, such as learning how to present and debate one’s ideas, when and how to compromise, and how to critically assess and synthesize different sources of information before coming to a decision, are critical for democratic life. Ideally, we’d be better at them than we seem to be today; we might improve if we gave ourselves the chance to work on such skills more often, between and beyond elections. Economic democracy—whether through participating in unions, electing work councils, voting as shareholding workers, or working in full-fledged cooperatives—gives us the opportunity to hone those skills at work, where we come together with people often very different from ourselves to achieve things big and small. Through work, democracy could be made more concrete to those who’ve come to doubt it—understood, materially, as the means by which raises can be won and problems in our daily working lives that trouble us can be solved, rather than as abstractions bandied about by politicians who always seem to promise more than they accomplish.

Take a stand against Trump and support The Nation!

In this moment of crisis, we need a unified, progressive opposition to Donald Trump.

We’re starting to see one take shape in the streets and at ballot boxes across the country: from New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani’s campaign focused on affordability, to communities protecting their neighbors from ICE, to the senators opposing arms shipments to Israel.

The Democratic Party has an urgent choice to make: Will it embrace a politics that is principled and popular, or will it continue to insist on losing elections with the out-of-touch elites and consultants that got us here?

At The Nation, we know which side we’re on. Every day, we make the case for a more democratic and equal world by championing progressive leaders, lifting up movements fighting for justice, and exposing the oligarchs and corporations profiting at the expense of us all. Our independent journalism informs and empowers progressives across the country and helps bring this politics to new readers ready to join the fight.

We need your help to continue this work. Will you donate to support The Nation’s independent journalism? Every contribution goes to our award-winning reporting, analysis, and commentary.

Thank you for helping us take on Trump and build the just society we know is possible.

Sincerely,

Bhaskar Sunkara

President, The Nation

More from The Nation

Yes, Texas Representative Nicole Collier Was Under “House Arrest” in the Texas Capitol Yes, Texas Representative Nicole Collier Was Under “House Arrest” in the Texas Capitol

Collier speaks about her surreal ordeal, wherein she refused to sign a permission slip and accept a police escort to leave the Austin statehouse and had to sleep there for two nig...

Democrats Need to Stop Letting Trump Set the Terms of Engagement Democrats Need to Stop Letting Trump Set the Terms of Engagement

With every White House action, from mass deportation to domestic deployment of federal troops the “opposition party” has accepted the premise and failed to offer an alternative.

Letter From DC: Goodbye to John Wall, Hello to Celebrating His Rebel Spirit Letter From DC: Goodbye to John Wall, Hello to Celebrating His Rebel Spirit

The former Washington Wizards point guard retires from the NBA, but the anti-Trump protests embody his swaggy defiance.

The DNC Chair Proposes Major Reforms to Limit Big Money The DNC Chair Proposes Major Reforms to Limit Big Money

Party building vs. candidate addiction has never been more urgent.

Solidarity Staircase Solidarity Staircase

The stairways to iconic Park Güell in Barcelona were transformed into a representation of the Palestinian flag , and the plaza above was named “Free Palestine”, as a symbol of supp...