Why Are So Many Mexican Mayors Getting Murdered?

A staggering number of mayors have been brutally killed in the past few years—and there’s no end in sight. What’s going on?

Relatives of slain Mayor Alejandro Arcos carry his coffin during his funeral service, one week after he took office, in Chilpancingo, Guerrero state, Mexico, Monday, October 7, 2024.

(Alejandrino Gonzalez / AP)The five assassins arrived on a warm Sunday morning in June, riding motorcycles and dressed all in black. They burst into the lime-green building that serves as the city hall of San Mateo Piñas, a small town in the lush hills of Oaxaca state in southern Mexico. They fired 60 rounds in six minutes: Afterward, the mayor, Lilia Gema García Soto, lay dead, the white floors splattered in blood. The killers then roared off again, vanishing into the emerald hillsides.

Soto was the first woman elected to the post and had vowed to root out the corruption that had plagued this village of some 2,000 people.

Among the motives being investigated for García’s killing is a federal complaint she had filed for the alleged siphoning off of about $1.25 million in hurricane relief funds by her predecessor. “She was a woman who always acted with integrity, with honesty,” said her son, Oscar Velásquez García, at her funeral. “She never gave in to blackmail, never played into the games of the corrupt, and that’s why they took these cowardly actions against her.”

Whatever the reason for García’s assassination, her murder is part of a horrifying national trend: Being a mayor in Mexico is increasingly tantamount to a death wish. Between the country’s extreme levels of generalized violence, as well as the growing involvement of powerful cartels in local politics, democracy in Mexico has become a deadly battlefield—and mayors are on the front lines. A recent report by the watchdog group Armed Conflict Location & Event Data named Mexico as the world’s most dangerous country for local elected officials, with 342 violent incidents reported in 2024. And there were 50 politically motivated killings in just the first three months of 2025, according to consulting firm Integralia.

García was one of eight mayors murdered across the country since October. Among them was Alejandro Arcos, mayor of Chilpancingo, a state capital, whose decapitated head was found on top of a white pickup truck, less than a week after he took office. And that doesn’t include the assassination in May of two top aides to the mayor of Mexico City, arguably the most powerful politician in the country after the president.

Even just running for office can be deadly: The week before the Mexico City murders, a mayoral candidate in the state of Veracruz was gunned down alongside four other people, including her own daughter. Throughout the 2024 election cycle, 18 mayoral candidates or aspiring candidates were assassinated. Meanwhile, during former President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s term, at least 87 mayors, former mayors, and mayoral candidates were killed. Although President Claudia Sheinbaum has made security a top priority of her administration and vowed to investigate some individual killings, such as that of Arcos, she has not specifically addressed the epidemic of mayoral assassinations.

“Democracy in Mexico is corroding. It’s being destroyed in many parts of the country,” said Eduardo Guerrero, a Mexican security analyst. “The electoral system is being perverted and corrupted.”

Untangling the reasons behind this surge in slayings is complex. Firstly, there is the generalized wave of cartel-fueled violence that has overtaken Mexico in recent decades, with public officials sometimes caught in the crossfire.

In 2023, there were more than 31,000 murders in Mexico. That’s a homicide rate over four times higher than in the United States. Making matters worse is Mexico’s abysmally weak criminal justice system, where only one in 10 murder investigations results in a conviction.

“Unfortunately, we’ve been in a situation for years where killing someone is seen as relatively easy,” said Cecilia Farfán-Méndez, head of the North American observatory at the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime. “There’s no real punishment for murder.”

Taking out a political rival, or silencing an anti-corruption crusader like García, becomes child’s play, because would-be assassins know that, in all likelihood, they will get away with it, especially at the municipal level where police forces are often corrupt and underfunded.

Yet the specific targeting of elected officials points to something more sinister: Namely, the involvement of organized crime in local politics.

In recent years, Mexican cartels have become extraordinarily powerful, controlling up to a third of the country, according to the US military. Maintaining this level of territorial dominance requires control not just of major highways but also of the backroads and dirt tracks where drugs and cartel foot soldiers can more easily pass undetected.

“You hear of municipalities where there isn’t even police, where these organizations come and go as they please,” said Saulo Dávila, senior consultant at Integralia. “Criminal organizations understand that they have to control the municipality…that’s going to guarantee that they can operate with much greater freedom.”

Cartels have also diversified their criminal portfolio beyond the drug trade, turning to more localized forms of criminal enterprise, such as extortion, fuel theft, and illegal logging.

This requires cooperation from local officials to either look the other way as cartels go about their business or, in some cases, to actively support them, including in the form of lucrative government contracts that are awarded to criminal groups. Mayors who refuse to cooperate end up becoming targets.

“Political violence is aimed at political actors who prove to be a hindrance to dominant criminal organizations,” said Guerrero, the security analyst. “Mayors in many regions of the country have to ask permission from criminal capos about state spending on important infrastructure projects that the municipality wants to undertake.”

Take the city of Iguala, in Guerrero state, one of Mexico’s most violent. Well-known for being the site where 43 students were violently disappeared in 2014, it remains deeply entangled with organized crime.

According to a 2021 Mexican military memo uncovered by the Guacamayas hacker group and obtained by The Nation, the mayor of Iguala at the time had received death threats from organized crime, but was planning on launching a reelection bid “with the aim of fulfilling commitments made to antagonistic criminal groups operating in the area.”

The mayor had apparently awarded five contracts worth 1 million pesos a month (about $50,000) to the Guerreros Unidos cartel, the same group widely believed to be responsible for the students’ disappearance. The memo also noted that, according to a protected witness, of the city’s 68 police officers, 40 had links to the Guerreros Unidos, working as sicarios or informants.

So while in some cases cartels may just be bribing public officials to turn a blind eye, security analysts say that increasingly in Mexico the state is becoming a tool for criminal groups to enrich themselves and expand their empire.

And in many parts of the country, making a deal with a cartel is the only way to run for office in the first place, according to Guerrero.

“If you want to be a candidate or seek reelection, the first person you need to ask for permission is the local crime boss,” he said. “If you don’t ask permission, you’re at risk of being assassinated at any moment.”

But if a rival cartel then seeks to take over that same territory, an elected official who made a deal with a different group might then become a target.

“These organizations don’t come in softly, they come in violently,” said Integralia’s Dávila. “Part of this violence involves threatening members of the municipal government, including the police and the mayor, to tell them, ‘Well, now I’m the one you’re going to obey.’ But if you already have an agreement with the other group, that’s where they end up between bullets.”

One man who has so far managed to avoid the cartels’ claws is Perseo Quiroz, mayor of Tepoztlán, a community of some 55,000 people about an hour and half south of Mexico City. A quaint cobblestoned town pressed up against dramatic cliffs that turn deep green and fill with waterfalls during the rainy season, Tepoztlán has long been a major tourist destination, as well as a weekend escape for wealthy residents of the nation’s capital.

Largely for those reasons, it has mostly avoided the narco bloodshed that has engulfed many other towns. Still, Quiroz, who is a former executive director of Amnesty International Mexico and ran as an independent, said he was repeatedly warned that the cartels would approach him during his campaign to make some kind of corrupt pact. That never happened, he believes, because no one thought he would win: Independent candidates in Mexico rarely do.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →That doesn’t mean Quiroz wasn’t fearful running for office, given the levels of political violence across the country: The year he ran was the most violent electorally in Mexico’s history.

“It would be crazy not to be afraid,” he said. “It’s like pain: Pain alerts you to certain things. You feel pain because something’s wrong. And to an extent being afraid forces you to take certain precautions. But that doesn’t mean that fear is going to paralyze you.”

After assuming office in January, Quiroz began implementing some of the reforms he had campaigned on: Shutting down bars that were blasting music late into the night; halting real estate developments run amok. But he also found himself in the middle of a crime wave.

In February, a group of about a dozen armed men burst into an upscale restaurant and demanded that the 40 patrons get on the floor. The bandits stole people’s cell phones and cash, as well as the restaurant’s safe. They smashed security cameras and beat up workers before fleeing back into the night in a black van and two motorcycles. The incident made national headlines.

Quiroz suspects that the surge in crime may have been a result of cartels’ trying to infiltrate Tepoztlán. “Since we didn’t make a pact with anyone, there were certain groups that I think were trying to work their way in,” he said.

The mayor has since replaced his head of security and begun working with state police as well as the military and the National Guard. In recent months, things have calmed down. “I’d like to think that we’ve been able to halt these attempts to take control of la plaza,” said Quiroz, using a term that means “the turf” in cartel lingo.

But a couple of weeks ago, the mayor received a threatening phone call from a man identifying himself as a member of one of Mexico’s major cartels. The man said they “didn’t agree with how the town was being run,” before adding, “Beware of the consequences.”

The phone call was traced to a major prison in Mexico City, which calmed Quiroz—to an extent.

“It pulls the rug out from under you a bit,” he said. “Everyone is telling me to be careful.”

Take a stand against Trump and support The Nation!

In this moment of crisis, we need a unified, progressive opposition to Donald Trump.

We’re starting to see one take shape in the streets and at ballot boxes across the country: from New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani’s campaign focused on affordability, to communities protecting their neighbors from ICE, to the senators opposing arms shipments to Israel.

The Democratic Party has an urgent choice to make: Will it embrace a politics that is principled and popular, or will it continue to insist on losing elections with the out-of-touch elites and consultants that got us here?

At The Nation, we know which side we’re on. Every day, we make the case for a more democratic and equal world by championing progressive leaders, lifting up movements fighting for justice, and exposing the oligarchs and corporations profiting at the expense of us all. Our independent journalism informs and empowers progressives across the country and helps bring this politics to new readers ready to join the fight.

We need your help to continue this work. Will you donate to support The Nation’s independent journalism? Every contribution goes to our award-winning reporting, analysis, and commentary.

Thank you for helping us take on Trump and build the just society we know is possible.

Sincerely,

Bhaskar Sunkara

President, The Nation

More from The Nation

Israeli Soldiers Abused Me Before. I’m Terrified That They’ll Do It Again. Israeli Soldiers Abused Me Before. I’m Terrified That They’ll Do It Again.

Israel is invading Gaza City again. The trauma of what they did to me and my family during their last invasion haunts me every single day.

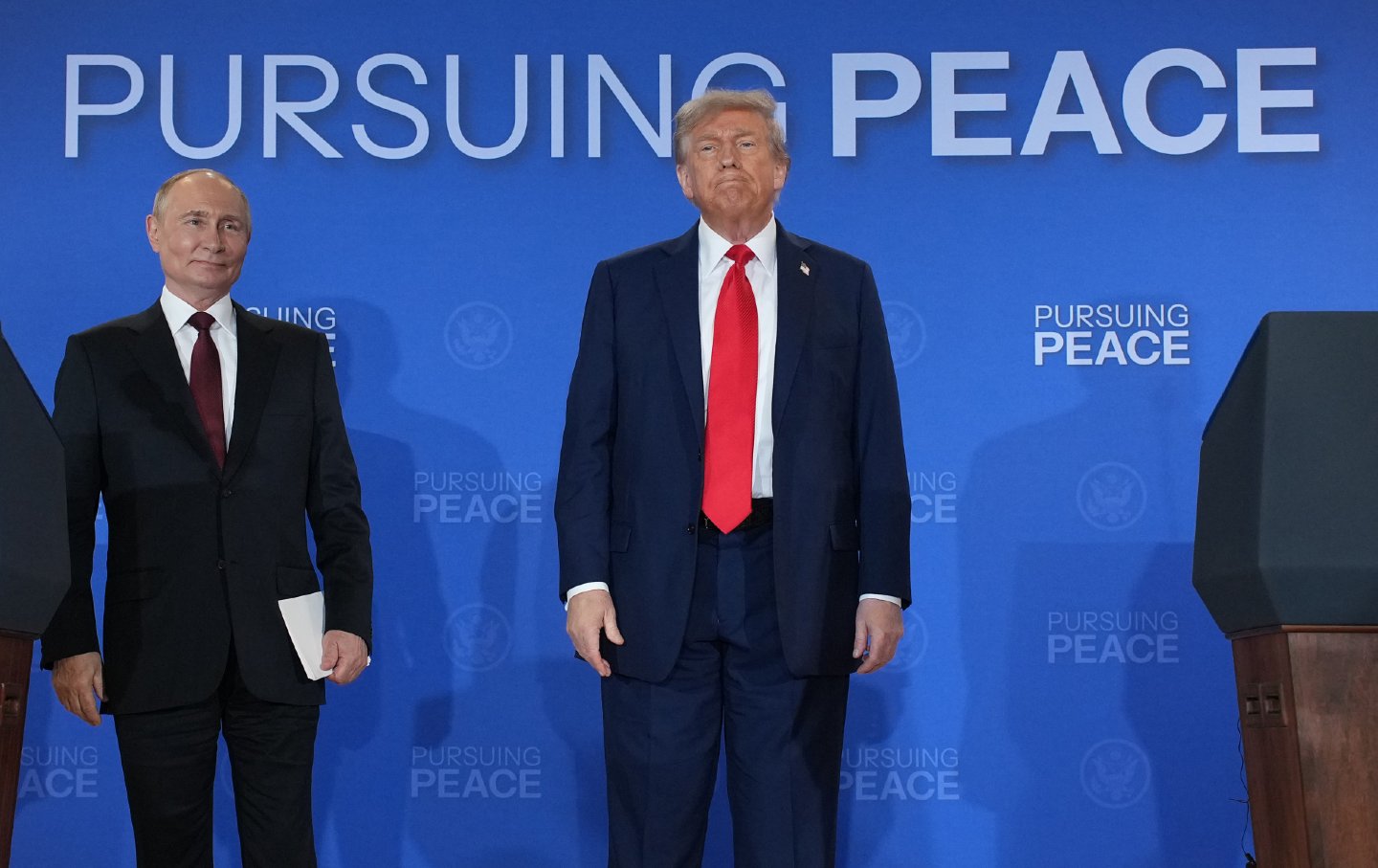

The Ukraine Peace Process Is Moving Quite Fast The Ukraine Peace Process Is Moving Quite Fast

Here are the openings—and obstacles.

Dismantling USAID Wasn’t Just Cruel—It Was Stupid Dismantling USAID Wasn’t Just Cruel—It Was Stupid

In an interconnected world, those who are alone, to use a favorite word of the president’s, are losers.

Trump Won’t Deliver Peace to Ukraine—or Anywhere Else Trump Won’t Deliver Peace to Ukraine—or Anywhere Else

No one can trust the United States when a fickle man-child controls its foreign policy.

Presidents Trump and Putin Must Seize the Moment in Alaska Presidents Trump and Putin Must Seize the Moment in Alaska

The war in Ukraine is a regional security and humanitarian tragedy, but regarding nuclear weapons, Washington and Moscow stand to benefit from working together.

The Bookstores Bridging Divides in Israel The Bookstores Bridging Divides in Israel

People of goodwill on either side of the horror find unity in the search for a good read.