“It’s Homeland or Death”: The Separatist Movement Roiling the Indian World

Indian Sikhs across the globe want to form an independent breakaway state called Khalistan. The Indian government wants to crush them by any means necessary.

Sikhs gather in London’s Trafalgar Square on the 41st anniversary of the attack by Indian government forces on the Golden Temple in Amritsar. Many in attendance carried yellow Khalistan flags.

(Mike Kemp / In Pictures via Getty Images)“On paper, we are at war with India,” Gurminder Singh told me, as thousands of people gathered on a cloudless March afternoon in Los Angeles. The international organization Sikhs for Justice (SFJ) had corralled Punjabis from across California to participate in the latest of many “Khalistan referendums.” What were they voting on? Whether they would support the formation of a sovereign Sikh state, Khalistan, carved out of the historical region of Punjab, which straddles the hyper-militarized border that separates India from Pakistan.

Singh is a coordinator for SFJ’s Australian and New Zealand chapters, which organize similar nonbinding referendums across the Pacific. Bespectacled, with a graying beard, he spoke methodically about what they hope to achieve through this process. If they remain on schedule, the results of the votes, gathered from the strongholds of the global Punjabi diaspora, will be presented to the United Nations in 2026. Depending on the results, he said, pro-Khalistan political bodies could move the case forward that the Punjabis residing within India’s borders are deserving of self-determination.

The only eligibility to vote in this particular exercise, Singh explained, was being ethnically Punjabi: Muslims, Hindus, and Christians were all invited to cast a ballot. But the vast majority of those present in LA were visibly Sikh. The line to vote snaked around the block, and reporters from Punjabi media outlets queried impassioned voters, who periodically burst into a call and response: “KHALISTAN! ZINDABAD!” “Long live the land of the Sikhs!” Vivid graphics were fixed to 18-wheeler trucks on the periphery of the space. One was a wanted poster for India’s political leadership, namely Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Another featured the bloodied, triumphant image of President Trump after his attempted assassination, superimposed above gleaming letters, “TARGETED FOR POLITICAL OPINION”— a nod to the complex political dynamics at play in California’s rural Sikh community.

The Khalistan movement first made global news when groups of Sikhs took up arms against the Indian state in the early 1980s, after thousands participated in years of nonviolent protest against the government’s disenfranchisement of rural Punjabis. Within India’s borders, Khalistan supporters are designated as terrorists, and the fight for independence has been squelched, as open sympathy is swiftly silenced or worse. In the diaspora, however, the dream never died, and has since repositioned itself as a political movement committed to a nonviolent and legal approach to agitating for Khalistan. California’s massive Central Valley, the highly conservative interior of America’s most “liberal” state, and now home to many of the West Coast’s hundreds of thousands of Sikhs, is one of the movement’s hubs.

In the United States, the movement’s organizing prowess makes it a tantalizing political bloc to court. Accordingly, some state and federal politicians whose constituencies comprise Sikh communities have bought into the movement, or, at the very least, advocate for the Khalistanis’ constitutional rights.

But the highly charged politics around Khalistan have followed the movement across the world. For supporters, commemorating the Khalistan movement, including its past armed factions, is an expression of their freedom. For critics, any support of Khalistan is an incitement to violence.

And the movement does face real threats. In 2024, the US Department of Justice alleged that an Indian government employee had attempted to assassinate SFJ’s main spokesperson, Gurpatwant Singh Pannun, in Manhattan, one year after the slaying of pro-Khalistan organizer and Canadian citizen Hardeep Singh Nijjar, whose killers Justin Trudeau accused of having connections to Indian intelligence.

The paranoia was palpable at the Los Angeles referendum. I seemed to be one of the only non-Punjabi reporters in attendance. Not a single voter agreed to speak with me, even anonymously, out of fear that their families in Punjab would be retaliated against. At one point, an organizer approached me with an eyebrow raised. His suspicion was momentarily quelled when I assured him I was an American, not an Indian, journalist, but in my periphery, I could see him scanning me. These fears reveal the depths of India’s unrelenting repression of political dissent, even in the diaspora.

Irrigating the Plains of Punjab With Blood

Sikhs make up less than 2 percent of India’s total population, and Khalistanis are an even smaller subset of that subset. Yet, for the past 50 years, the fight for a sovereign Sikh nation has successfully challenged the logic of India’s borders enough to warrant immense state repression anywhere on the planet that the flag of Khalistan is hoisted.

The story of the Sikhs, and eventually, Khalistan, begins in Punjab—panj āb—or “five waters,” the Farsi term for the region that references the five rivers that run through it. Not every Punjabi is Sikh, but nearly every Sikh is Punjabi. The Sikh religion was founded in Punjab in the 15th century, largely in opposition to the hierarchical aspects of both Hinduism and Islam. At its height, the Sikh empire extended as far as Tibet. In 1849, Sikhs were defeated in the Second Anglo-Sikh War, and Punjab was annexed into British India. For many Khalistanis, resurrecting the glory of the Sikh Empire is fundamental to establishing an independent Khalistan. In this framing, the British colonial period and the current Indian state are two interruptions in an older continuum of Sikh history.

In 1947, amid the catastrophic partitioning of British India, Punjab was given a choice: remain whole and join the emerging Islamic Republic of Pakistan, or divide along religious lines into Muslim and non-Muslim entities, the latter of which would accede to the secular democracy of India. It was a particularly complicated decision. Colonial Punjab, a contiguous province of some 34.3 million people that sprawled across parts of what are now India and Pakistan, was roughly evenly split between Muslims and non-Muslims; 15 percent of the population was Sikh.

On June 23, the Punjab Provincial Assembly voted that the province would be split. The following day, The New York Times reported that the old Punjabi city of Lahore (now in Pakistan) was gripped by religious riots described as “holocausts.” One-sixth of its neighborhoods were reportedly destroyed.

Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs were subject to retributive massacres across the whole of the province up until independence—August 14 for Pakistan, and August 15 for India. Millions of Sikhs and Hindus in the western part of Punjab headed east toward India, and Muslims in what is now India made the opposite journey. Entire train cars of refugees were set alight, and many who made the journey on foot died along the way.

Over the next two decades, the Indian territory of Punjab would undergo more geographic rezoning. In 1966, a new Hindi-speaking state, Haryana, was carved out of the southeast. The northern third of the state became Himachal Pradesh. As a result, Sikhs now constituted a demographic majority in what was left.

The peasant masses of the diminutive state relied almost entirely on an agricultural economy. Championed by the central government in Delhi and the Ford Foundation, the industrialization of Punjabi agriculture (monocropping, introduction of seeds produced by Monsanto, and modern chemical fertilizers, otherwise known the Green Revolution) enriched the state’s economy and crop yield dramatically under the auspices of wealthy farmers, and helped India on its journey from British colony to modern nation-state. But it plunged much of Punjab’s Sikh peasantry into bottomless debt, as they had to borrow more and more to keep up with the demand of an industrial market. For thousands, all that was left to harvest after the growing season was more wealth disparity, endemic unemployment, and a florid resentment for the central government in Delhi.

Sikh politicians did attempt to appeal to the Indian government for greater autonomy in Punjab. In 1973, the political party Akali Dal promoted the Anandpur Sahib Resolution, which detailed a list of political and cultural demands for an “autonomous Sikh region” within India and greater rights for all the nation’s minorities, stopping short of agitating for an independent state. This went unheeded.

By 1984, several crucial events had rocked the land of five waters, and indeed the entire nation.

From 1975 to 1977, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared a state of emergency, allegedly for “internal disturbances,” as her political future was called into question amid allegations of election fraud. Thousands upon thousands of political opponents were swept up in mass arrests.

Then, in 1978, an intra-Sikh massacre, in which a heterodox sect and riot police opened fire on a group of orthodox Sikhs during a heated confrontation, ended in an acquittal of the perpetrators on all charges, prompting many orthodox Sikhs to conclude that the Indian state was incapable of delivering justice if Sikh blood were spilled. With that came the rise of the charismatic religious leader Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, posthumously erected as the father of the Khalistani guerrilla movement and cherished shaheed (martyr). Bhindranwale did not engage in combat and was never a strict proponent of a separate Khalistani nation, but he mobilized the masses to agitate for greater autonomy in Punjab while encouraging Sikhs to be baptized and to arm themselves.

In the years leading up to 1984, clashes erupted regularly between protesters, militants, and police in Punjab and Delhi. Scores of civilian protesters were gunned down by Indian police. The launch of a grassroots movement demanding a decentralized government that empowered individual states like Punjab was met with mass arrests. And accordingly, multiple militarized factions germinated in Punjab, not always unified in their armed struggle.

Unarmed Punjabis of all faiths fell under fire from both state and non-state actors. Insurgent militants robbed banks, raided armories, and attempted to cripple the state’s transportation infrastructure. In 1983, the police crackdown ordered by the state’s Chief Minister (and Sikh) Darbara Singh detained and murdered youths with complete impunity. Sikhs in other parts of India were routinely profiled as possible guerrillas regardless of their convictions about armed resistance. Bhindranwale, by now a folk hero, was vindicated in his call for Sikh self-defense in the minds of many.

On a blazing summer night in June of 1984, this tension boiled over like a pot of milk. Acting on intelligence that Bhindranwale and other guerrillas had fortified the Darbar Sahib (the most important gurdwara, or Sikh temple, in India) with weapons, Prime Minister Gandhi deployed the Indian army in a devastating raid on the temple. Inside the temple, guerrillas were prepared for a long and fierce stakeout.

A battle raged over the next ten days. The house of God was reduced to a house of charnel. At the time of the raid, thousands of pilgrims were also visiting the complex for the “martyrdom day” of an important Sikh guru. An Indian white paper tallied the civilian casualties at a scant 493, but estimates based on eyewitness testimonies ranged from 1,600 to 6,000. The sanctum sanctorum sustained heavy damage, countless historical objects were burned, and the carnage evoked the historical memory of Sikhs who had been brutalized by the Mughals centuries ago. The corpses of several martyrs, including Bhindranwale, were pulled from the smoking heap. For many, this was a declaration of war, one ominously forecasted by Bhindranwale himself. He famously said that should the Indian army ever defile the holy site, “the foundations for Khalistan would be laid.”

A chain reaction ensued. Months later, two of Gandhi’s Sikh bodyguards unloaded a revolver and a submachine gun into her. In the days following, anti-Sikh “riots,” or more aptly, an organized pogrom, engulfed the Indian capital. In plain sight, and with the full complicity of police, Sikhs were burned alive by mobs in the streets. A conservative estimate of 6,000 perished.

The bloodshed continued into the next decade. In tandem with the uprisings in nearby Kashmir, the Indian government has maintained that Pakistan provided shelter, arms, and training to guerrillas in Punjab. Pakistan’s alleged financial support of the Khalistanis mirrors its accusation that India has fueled the ongoing Baloch independence movement in Pakistan, and Delhi’s pivotal role in the liberation of the Bangladeshis in the 1970s, from their despotic rulers in Islamabad. In all these contexts—from Khalistanis to Kashmiris, Balochis to Bangladeshis—real popular movements (all likely supported by external governments to certain degrees) are purposefully reduced to proxy squabbles between the subcontinent’s two endemically corrupt and hegemonic powers.

The dream of Khalistan is articulated in the tenets of the Sikh faith, and for many fighters, their struggle was devotional, rooted in the religion’s early history. Khalistan is derived from the word khalsa, or pure, which now refers to devout, baptized Sikhs but was first used in 1699 to describe the regiment of the faithful who defended their community, politically and militarily. Yet many Sikhs themselves were the victims of guerrilla violence during the height of the insurgency, fought on behalf of the counterinsurgency, and were invested in Punjab’s remaining a part of India. Those who did join the guerrilla movement felt that they were backed into a corner by the impending brutality of the Indian state, and saw armed struggle as their only chance of survival.

By the mid-1990s, Indian security forces had tortured, murdered, or forcibly disappeared many thousands of innocents. In conjunction with the targeting killing of political figures, insurgent militants bombed civilian areas, killed, abducted, and extorted money from noncombatants, and at times conflated Hindus with agents of the Indian state. Most infamously, a group of Canadian Sikhs belonging to the Babar Khalsa International was implicated in the downing of passenger flight Air India 182, which plunged into the North Atlantic in June of 1985. All 329 people were killed, their bodies salvaged from the sea off the coast of Ireland. Controversially, the two main suspects were acquitted by a Canadian court for lack of evidence—most believe because of the testimony of a key witness, found guilty of perjury 25 years after the trial, while few have ventured to claim that the Indian government may have been involved in the terrorist attack itself.

By the mid-1990s, many militants had been killed, imprisoned, or surrendered, and by the 1997 election, moderate Sikh leadership rose to power by popular support. There is no active insurgency in Punjab today, beyond sparse and isolated incidents over the past decade. A wave of assassinations in 2016 led Indian police to baselessly arrest and allegedly torture a Sikh British national after his wedding day in Punjab, where he remains in Indian custody and solitary confinement despite his being acquitted of terrorism charges. And most recently, amid the mass deployment of ICE, a man in Sacramento was deported and extradited to India for his alleged connection to a series of grenade attacks, one of which targeted a retired Punjabi Police officer.

The Indian government has failed to take meaningful accountability for its “decade of disappearances” that wounded parts of Punjab interminably, prompting many Sikhs, both in India and around the world, to remain convinced of the absolute necessity of a Khalistani state. Given the current situation, it may be impossible to accurately gauge support for the movement among the people of Punjab. The dominant narrative says that fervor for Khalistan lives only in the hearts of those in exile, rather than people living within India’s borders. But this could be somewhat complicated by the popularity of those rare politicians who have expressed pro-Khalistan views ahead of their election campaigns—and won.

How is it that pro-Khalistani politicians can run for office in India? Political philosopher and scholar of Sikh studies Dr. Prabhsharanbir Singh put it this way over the phone: “India is an extremely complicated political entity.” It is neither exclusively fascist nor a true democracy, he said; in fact, it’s both. In Singh’s estimation, India’s central government tolerates a select few pro-Khalistan voices in Punjab’s political machinery because it gives credence to Indian democracy, but with the police state at its command, these popular victories will have no real effect on the possibility of sovereignty.

He is confident, however, that there is currently a pro-Khalistan wave in Punjab, concentrated mostly in working-class, Sikh-dominated, rural parts of the state. This is in part due to the circulation of information that was tightly controlled before social media and a growing consensus that the BJP is more antagonistic toward the nation’s minorities. According to Singh, there is no doubt that some elite circles of Sikhs in Punjab are still opposed to the idea of Khalistan on a fundamental level, but many others are simply unwilling to sacrifice another generation of youths. Fear of the consequences, he said, is not true opposition to Khalistan.

Trouble in the Valley

If you drive long enough up the I-5 freeway near Stockton, you may see an 18-wheeler with a painted mural of Sikh shaheedi, clad with a sword or spear.

It was here that America’s first gurdwara was established in 1912, when Sikh laborers, like their Chinese and Mexican counterparts, immigrated to California to work the rails and verdant croplands. It was here that Sikhs joined the Ghadar Party, a revolutionary movement against British Colonialism with strongholds in the Canadian, American, and Chinese diasporas. And it is here that some congregants continue to mobilize around the Khalistan movement. The Stockton Gurdwara proudly flies the mustard yellow Khalistani flag and organizes ceremonies commemorating martyred guerillas of various military outfits, unequivocally considered terrorists in India: the Khalistan Commando Force, the Khalistan Liberation Force, the Khalistan Tiger Force, Babbar Khalsa, and Sikhs living in the US who returned to Punjab to die on the front lines of what they understood to be a revolution against Indian neocolonialism.

In the mid 1980s, before the Khalistani armed struggle fizzled out, some fighters did migrate to the United States through both official and unofficial means, and at times planned to recruit sympathizers in established safehouses—according to declassified CIA reconnaissance, (which, as with most things connected to the CIA, should always be taken with a grain of salt).

Khalifornia’s contemporary Khalistan movement is unarmed and rooted in the political process. India’s accusations of some kind of direct connection between the diaspora and militancy have not been proven to any kind of legal standard, much to the chagrin of Khalistan’s critics.

Sikhs For Justice got its start by filing multiple lawsuits against Indian politicians whom SFJ alleged were involved in the violence of 1984. It soon grew to be the largest mobilizer of pro-Khalistan demonstrations and referendums in the world, eventually designated a terrorist organization in India. SFJ is especially known for its controversial, razor-tongued leader Gurpatwant Singh Pannun, who has taken aim at the whole of the Indian political establishment, from the sitting prime minister to the Dalit reformer who wrote the Indian constitution. The US State Department has yet to buckle under Indian pressure to designate him a terrorist, having previously defended SFJ’s First Amendment rights.

“They want us to follow the path of terrorism, which we will not,” activist and accountant Bobby Singh told me, from an administrative office at the historic religious site in Stockton. Tall and very serious-looking for just 25 years old, Singh is part of a new generation of young Californians engaged in what he described as “lobbying for the Khalistan movement.” But educational programming and community outreach are only part of the picture. A broad swath of Sikh Americans, who may or may not support the Khalistani cause, have championed other political causes on behalf of their community in large and small ways. Last year, Sikh Americans marched 350 miles through the heart of the Central Valley to demand that Congress designate the events of 1984 as a genocide. In January, Jaswant Singh Khalra Elementary School opened its doors to the children of Fresno, the first to be named after the Sikh human rights activist who exposed the illegal murder and cremation of thousands of Punjabis during the insurgency, only to be forcibly disappeared himself.

Even if today’s Khalistan supporters in the diaspora have opted for the pen over the sword, there is credible evidence that the long arm of Indian repression has come to the West.

Shortly after three Indian nationals gunned down the Khalistan activist and Canadian citizen Hardeep Singh Nijjar, Bobby began to receive ominous texts on his cell phone, warning him that he was next. Many, including then–Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, believed the Indian state had some role in Nijjar’s assassination, an accusation that Prime Minister Modi denied. Nijjar’s face has joined the placards of martyrs at Khalistan rallies and religious gatherings in rural California, 100,000-strong and growing.

Over the next year, the FBI investigated similar occurrences in the Bay Area and Manhattan, where federal law enforcement foiled a murder-for-hire plot targeting the world’s most forward-facing advocate of Khalistan, SFJ’s Pannun. An unsealed DOJ indictment named the primary suspect as Indian citizen Vikash Yadav. Yadav once served in the Central Reserve Police Force, a group of paramilitary squads deployed across the country that has systematically committed arbitrary killings against enemies of the state across India. The violent targeting of Khalistanis rattled the larger Sikh community. It also prompted politicians into action on the state and federal levels, both Sikh and non-Sikh. Just this year, the California Assembly introduced a bill that would instruct police officers how to identify transnational repression, drawing both support from a coalition of Sikhs and Hindus and fierce condemnation from other Hindu American organizations who fear that such legislation could target them for speaking out against the Khalistani cause. And more generally, preventing India from harming US citizens (and thereby, US sovereignty) isn’t exactly a left-or-right issue. It addresses a blatant violation of international law, recognized by both Democratic Senator Adam B. Schiff and ardent Republican Harmeet Dhillon.

However, Pannun’s botched assassination attempt in New York was anything but chilling. As it often does, history repeated itself, and the Indian prime minister’s heavy hand only drove people further toward dissent.

“There’s a reason why within India, there’s 238—plus separatist movements, right?” Bobby Singh asked rhetorically. This number may be impossible to accurately quantify, but it is indisputable that armed struggles of every stripe have been launched internally against the Indian state. By Bobby’s logic, India will inevitably Balkanize. So until then, he said, “it’s homeland or death.”

Saffron and Mustard

In the langars and prayer halls of certain gurdwaras across the Golden State, it is difficult to distinguish between men and shadows. For example, in the process of reporting this piece, a source told me that someone I happened to have a meeting with in the coming weeks was possibly an informant for the Indian government. Multiple interviewed subjects felt certain that their temples were being infiltrated by bad actors. “Anyone can grow a beard and pretend to be a Sikh,” one doctor remarked wryly over a cup of chai near the Oregon border. He claimed that other members of his small congregation, who work menial jobs at gas stations, pull into the temple parking lot with flashy sports cars clearly above their pay grades. “Where could they be getting the money for that?” he asked with a knowing look.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →A Sikh Californian’s rejection of their visa to travel back to Punjab could or could not be an indication that the Indian consulate in San Francisco is watching them. However, a threatening phone call from an Indian number in the middle of the night is less ambiguous, as described by one source who spoke on the condition of anonymity. After all, vocal critics of the Modi government, journalists and scholars in particular, have been known to have their “overseas citizens of India” statuses revoked. How widespread this kind of surveillance is hard to determine, but given what has been exposed through recent reporting, at least some of their worries are plausible.

It could be said that Sikh, Islamic, and Hindu nationalisms all follow the disastrous logic of partition, the reason for which many Indians of all faiths fundamentally reject all of the above.

The secular Indian National Congress dominated Parliament for 54 of the 78 years India has been free, and under their purview, both Khalistani and Hindu nationalist political parties have been banned at different points, their leaders either imprisoned or killed. One viewpoint that many in the BJP and Khalistanis seem to share is that Indian secularism was an abject failure, and the Congress Party nothing more than a despotic regime. However, casting aside the viability or moral solvency of religious statehood, only one of these nationalisms is grounds for imprisonment on charges of sedition, if not extrajudicial killing.

It is a fact that Gandhi’s socialist government directed the purge of Punjab on the grounds of a militarized secularism, but in today’s India, Modi and the Hindu right wing are the primary faces of Indian state terror. As the veneer of secular democracy has crumbled, it is Hindutvatis who have inherited the nation, and whose acolytes in the diaspora can freely declare their triumph without fear of transnational retaliation—as is their First Amendment right. Just as some politically active Sikhs continue to carry their struggle with them across oceans, so too do their adversaries. While the barrel of a gun may loom in the background, Khalistanis are also engaged in an information war with right-wing Hindu organizations made up of fellow immigrants. The fight between Khalistan and the Hindu Rashtra, David and Goliath but two religious nationalisms nonetheless, has reproduced itself in the diaspora.

The American “Sangh,” which translates loosely to “assembly,” is what political researchers have termed the matrix of multiple Hindu American nonprofits with ideological ties to Hindu nationalist politicians and paramilitaries in India. And amid the global targeting of Sikhs in recent years, tensions have mounted between some Sikh and Hindu communities over the issue of Khalistan, particularly in California. In lockstep with the increasingly ersatz Indian mediascape, leaders from certain Hindu organizations, such as the Hindu American Foundation, have publicly alleged that the movement in Khalifornia is hardly distinguishable from Punjabi gang violence in Canada, openly admitting that there are no established connections but claiming “it’s certainly plausible to connect the dots.” The Hindu American Foundation has worked closely with Modi’s administration to coordinate his visits to the US and has argued for Indian interests in Washington. When asked if this speculative criminal insinuation between Khalistanis and organized crime was part of their institutional position on the movement, HAF declined to answer.

And in tandem with the targeted repression of pro-Khalistani Sikhs on behalf of an avowedly Hindu nationalist government in India, Hindu temples in California have been defaced with anti-Modi graffiti, including a spray-painted slogan invoking Bhindranwale. This may be unsurprising given the rhetoric espoused by both the leader of Sikhs for Justice and the Hindu right wing: that the future of India is inextricably linked to Hinduism, and that its quest as a self-professed Hindu nation will necessitate the marginalization of religious minorities. If one were to take either of the most extreme ends at face value, it would be hard to glean that there are Sikhs who do not support Khalistan and Hindus who are anti-BJP. But the operative difference is that Khalistanis see themselves as stateless in the shadow of recent and immense violence; the project of Hindu supremacy is largely on the offensive with major political and popular support in India.

The general maligning of pro-Khalistan organizers in the US as drug traffickers, terrorists, and as contradictorily outcasted and central to the identity of the Sikh American communities is what the human rights attorney Arjun Sethi calls “diffused” transnational repression. “The Indian government is increasingly using institutions and individuals in the United States to peddle and produce disinformation about Sikh, Muslim, Dalit, and even Hindu allies who dare to critique the Indian government,” he explained.

Taking a bird’s-eye view, Sethi said, “peaceful Sikh organizing serves as a convenient bogeyman for the Indian government, whose Hindutva nationalist ideology is always looking for the next national security threat to mobilize their base.” There is no question many Sikhs are supportive of total sovereignty, he said, but that “Khalistan means different things to different people.” Included are those Sikhs who do not believe in a separate state, but march alongside devoted Khalistanis anyway.

“They show up at protests and speak out because they want accountability for the human rights atrocities that Sikhs have experienced for decades, for which there has nearly always been impunity.” And it is a combination of this ongoing impunity with the BJP’s fragility in the face of unfettered opposition, Sethi said, that would prompt the Indian government to so blatantly violate international law by executing foreign nationals.

This nuanced position toward the Khalistan question is also reflected in some of the most influential American Sikh organizations, such as the Sikh Coalition, which does not take an official position on the question of an independent Sikh state. Like some of the individual protesters described by Sethi, these institutions are more focused on protecting the civil rights of all Sikhs, including pro-Khalistan voices, while rejecting the conflation of the whole of Sikhism with Khalistan, and those American Khalistanis with criminal activity or terrorism. And, the Coalition clarified by e-mail, they do not align themselves with those who make a pejorative distinction between Sikhism and Khalistan—more simply put, they repudiate the common argument that no “real” Sikhs are pro-Khalistan.

On a quiet street in Fremont is an outspoken gurdwara, whose façade is plastered with large-scale signage eulogizing Khalistani shaheedis, including the Canadian Nijjar, and messaging for a summer protest at the Indian consulate near San Francisco’s glittering Salesforce tower.

I was reading a mural about the massacre of 1984 when I was greeted by a community activist, who asked to be referred to as simply Mr. Singh, out of fear of transnational repression. I was expecting our conversation to be one-on-one, but when we walked upstairs to the boardroom, we were joined by four other men and the 17-year-old daughter of one of them, her turban marking her as a baptised Sikh. When I asked if I could record our group interview, Mr. Singh made the same request. Consistent with other interviews for this story, these sources seemed as curious about me as I was about them, inquiring about my ethnic background in India or if I had ever personally felt like a second-class citizen while visiting.

A far cry from the RICO terror network that Indian media has projected onto Khalistanis in California, the leaders of this particular temple have framed themselves—and their vision of Khalistan—in ideological opposition to all aspects of Modi’s saffron authoritarianism. This extends beyond their agitations for an independent Sikh state. In 2023, the California legislature nearly passed SB 403, a bipartisan bill that would have enshrined lower castes and Dalits as protected categories, had Governor Gavin Newsom not vetoed it at the 11th hour. Right-wing Hindu organizations called the bill and its supporters “Hinduphobic,” while an interfaith coalition of Hindu, Sikh, and Muslim organizations endorsed it.

“Most Sikhs, we don’t believe in the caste system. We outrightly reject it,” Singh said. He described his support of SB 403 as rooted in the tenets of the Sikh faith, which explicitly reject caste (though in practice, the hierarchical system rooted in Hindu scripture does linger among some Sikh communities in India). But he explained that the participation of vocal Khalistanis in anti-caste demonstrations was used by critics to muddy the waters of the bill, as if a political issue with the support of a Khalistani reveals some kind of guilt by association.

“Oh, now Khalistanis are joining the protests… it [carries] a terrible meaning,” he explained. “A person can be a Dalit, but it doesn’t mean that they’re a Khalistani.” This pattern of demonizing larger political movements whose support base may include Khalistanis is consistent with the way the Indian government repressed farmer protests in 2021, when men carried the mustard flag among the varied masses of Indians robbed of their livelihoods by an increasingly privatized agricultural industry, a half-century after the Green Revolution. Many Khalistanis’ ancillary solidarity with the political struggles of Kashmiris, other minority groups in India, and even Palestinians could seem contradictory given that the movement’s most outspoken leader has aligned himself with Trump. But just as the Sikh diaspora is not a monolith, nor is Khalistan’s support base in Khalifornia, whose lived politics in the United States range from right to left, urban to rural, and often across class barriers. This strategic mutability is perhaps, in part, why pro-Khalistan organizations have garnered enough supporters to be considered a major national security threat from thousands of miles away, even if the movement is portrayed as “fringe” among Sikh communities.

When the interview ended, the inquisitive young woman who attentively observed our conversation offered to give me a tour of the complex’s community services. As we ambled through the gurdwara grounds, she told me that her father, a volunteer at the temple, was excited about the prospect of speaking with a reporter, and wanted her to sit in. She showed me their free clinic, the many classrooms where students of all ages learn Punjabi, and of course, the temple canteen. What seemed to be more than 100 portraits of martyrs stared down at congregants as they enjoyed hot rotis and a tart yogurt curry. Possibly the most haunting was the sole woman, Bibi Davinder Kaur Bholi. She was part of a team that kidnapped a Hindu businessman’s son in 1990. Months before she perished, her brother had been forcibly disappeared. At just 19 years old, she swallowed a cyanide capsule while policemen encircled her house.

Take a stand against Trump and support The Nation!

In this moment of crisis, we need a unified, progressive opposition to Donald Trump.

We’re starting to see one take shape in the streets and at ballot boxes across the country: from New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani’s campaign focused on affordability, to communities protecting their neighbors from ICE, to the senators opposing arms shipments to Israel.

The Democratic Party has an urgent choice to make: Will it embrace a politics that is principled and popular, or will it continue to insist on losing elections with the out-of-touch elites and consultants that got us here?

At The Nation, we know which side we’re on. Every day, we make the case for a more democratic and equal world by championing progressive leaders, lifting up movements fighting for justice, and exposing the oligarchs and corporations profiting at the expense of us all. Our independent journalism informs and empowers progressives across the country and helps bring this politics to new readers ready to join the fight.

We need your help to continue this work. Will you donate to support The Nation’s independent journalism? Every contribution goes to our award-winning reporting, analysis, and commentary.

Thank you for helping us take on Trump and build the just society we know is possible.

Sincerely,

Bhaskar Sunkara

President, The Nation

More from The Nation

Israeli Soldiers Abused Me Before. I’m Terrified That They’ll Do It Again. Israeli Soldiers Abused Me Before. I’m Terrified That They’ll Do It Again.

Israel is invading Gaza City again. The trauma of what they did to me and my family during their last invasion haunts me every single day.

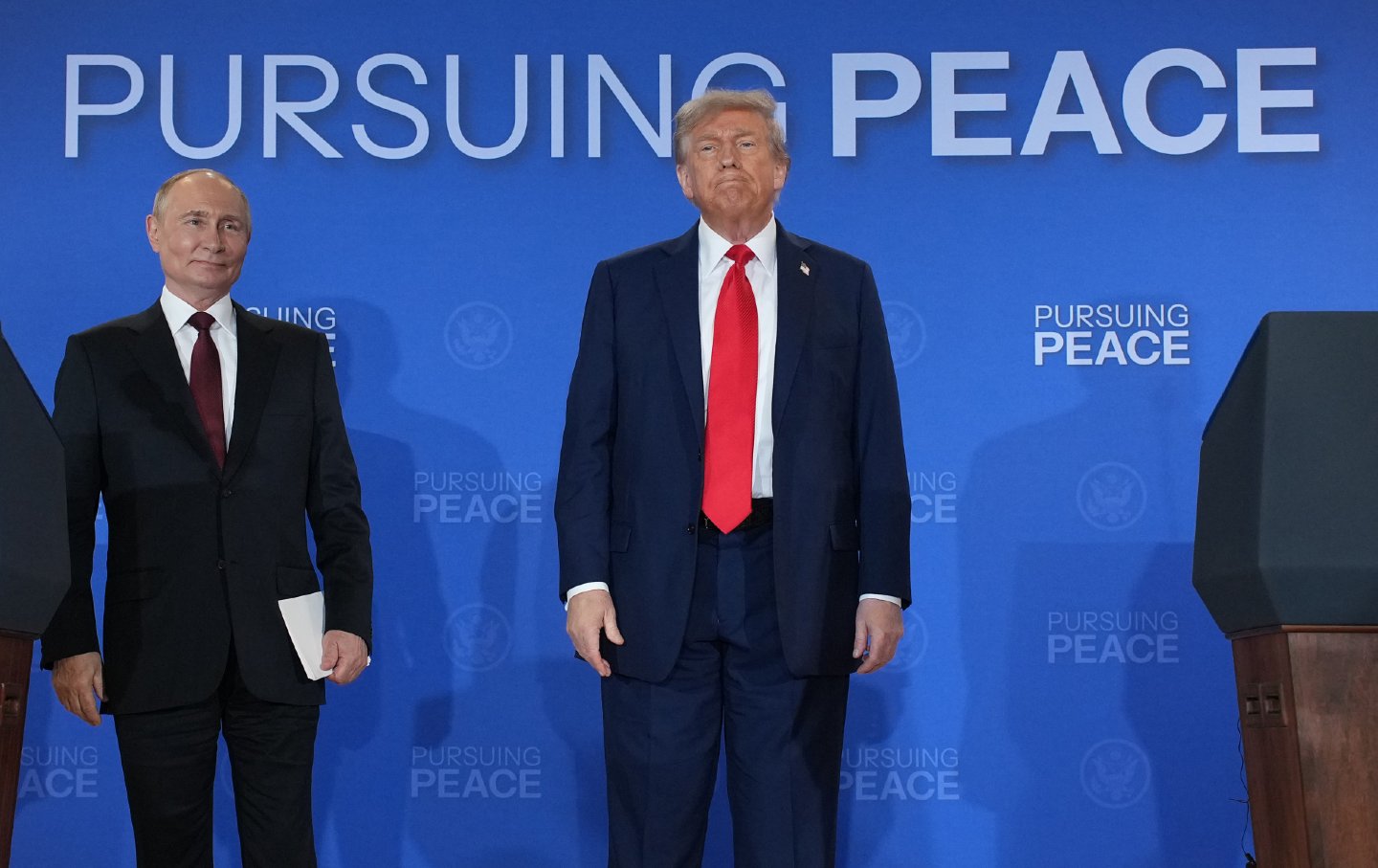

The Ukraine Peace Process Is Moving Quite Fast The Ukraine Peace Process Is Moving Quite Fast

Here are the openings—and obstacles.

Dismantling USAID Wasn’t Just Cruel—It Was Stupid Dismantling USAID Wasn’t Just Cruel—It Was Stupid

In an interconnected world, those who are alone, to use a favorite word of the president’s, are losers.

Trump Won’t Deliver Peace to Ukraine—or Anywhere Else Trump Won’t Deliver Peace to Ukraine—or Anywhere Else

No one can trust the United States when a fickle man-child controls its foreign policy.

Presidents Trump and Putin Must Seize the Moment in Alaska Presidents Trump and Putin Must Seize the Moment in Alaska

The war in Ukraine is a regional security and humanitarian tragedy, but regarding nuclear weapons, Washington and Moscow stand to benefit from working together.

The Bookstores Bridging Divides in Israel The Bookstores Bridging Divides in Israel

People of goodwill on either side of the horror find unity in the search for a good read.